"If you’re a public figure," says Rod Stewart, "you’ve got to enjoy being in the public. If you don’t, then fuck off!"

A revealing post-prandial chat with the eternal superstar. (It was 1993. It feels like yesterday.)

Fame changed Rod Stewart. It turned him into the person he always wanted to be. It turned him into the kind of singer who could insert an image of himself into a vandalised version of Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette on the cover of A Night On The Town. “How poncey!” Rod will tell me later. “I don’t know how I got away with it.”

Rod came from a less apologetic time - a time when being a pop star was like being a footballer - a dream no more plausible than winning the pools. Being Rod Stewart was like being George Best. Which may be why I spent so much time trying to get him to explain where it all went wrong.

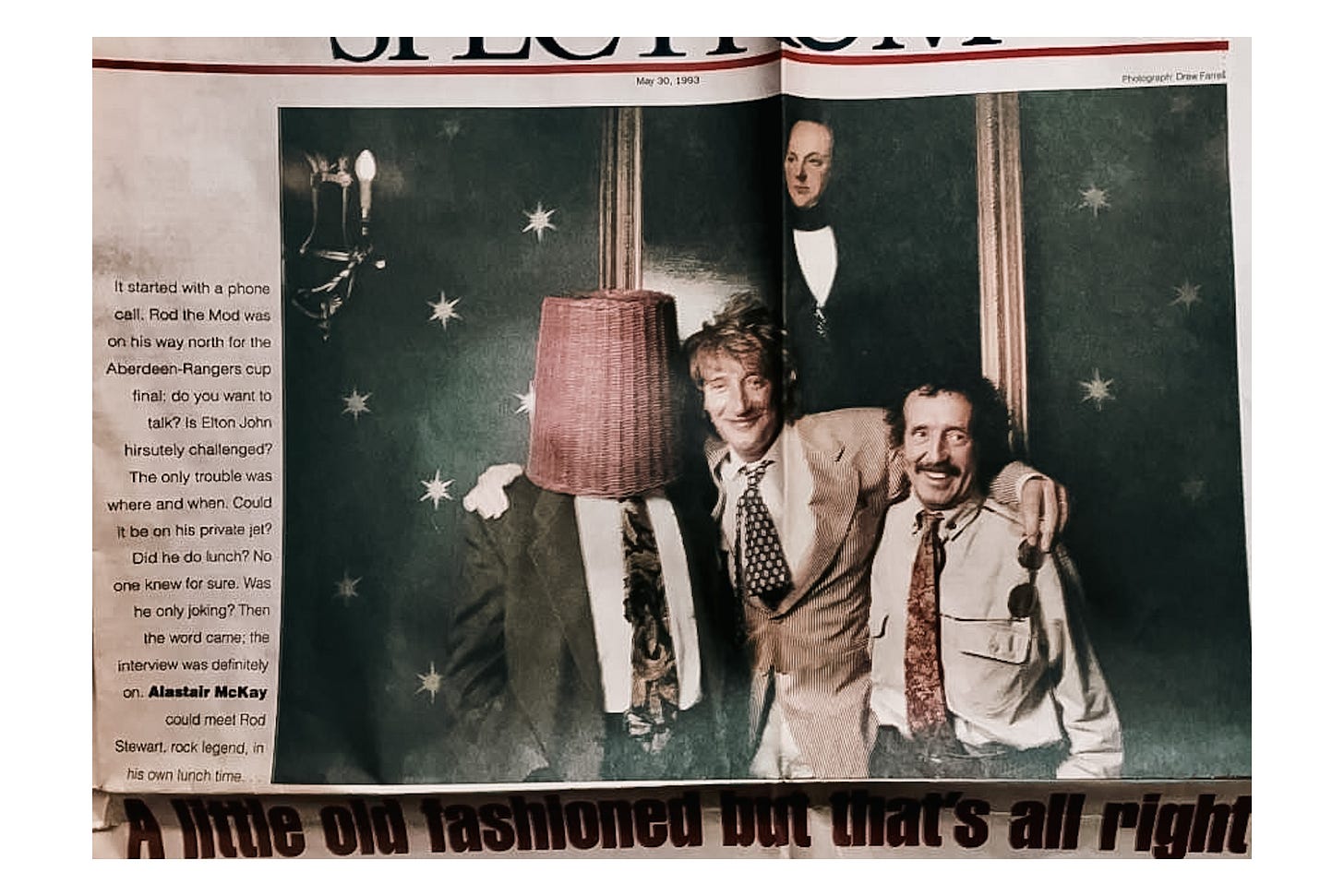

My interview with Rod was uncertain. It was hard to get a precise answer about the where and when. All I knew was that Rod was flying in for the Scottish Cup final between Rangers and Aberdeen at Celtic Park and I’d hear more later. My editor was in raptures. I started the week imagining I would have an age to write the story - honing, whittling, draining it of spontaneity - given that the interview was likely to take place on a Saturday and the features section was completed by Friday night.

No. Rod was a special case. Superstar logic applied. For the first and perhaps only time, the front page of the features section was to be held. My interview was to be treated like a match report.

Obviously I complained. An hour to write 2000 words. It wasn't possible. These complaints had the effect of making the editor more enthusiastic.

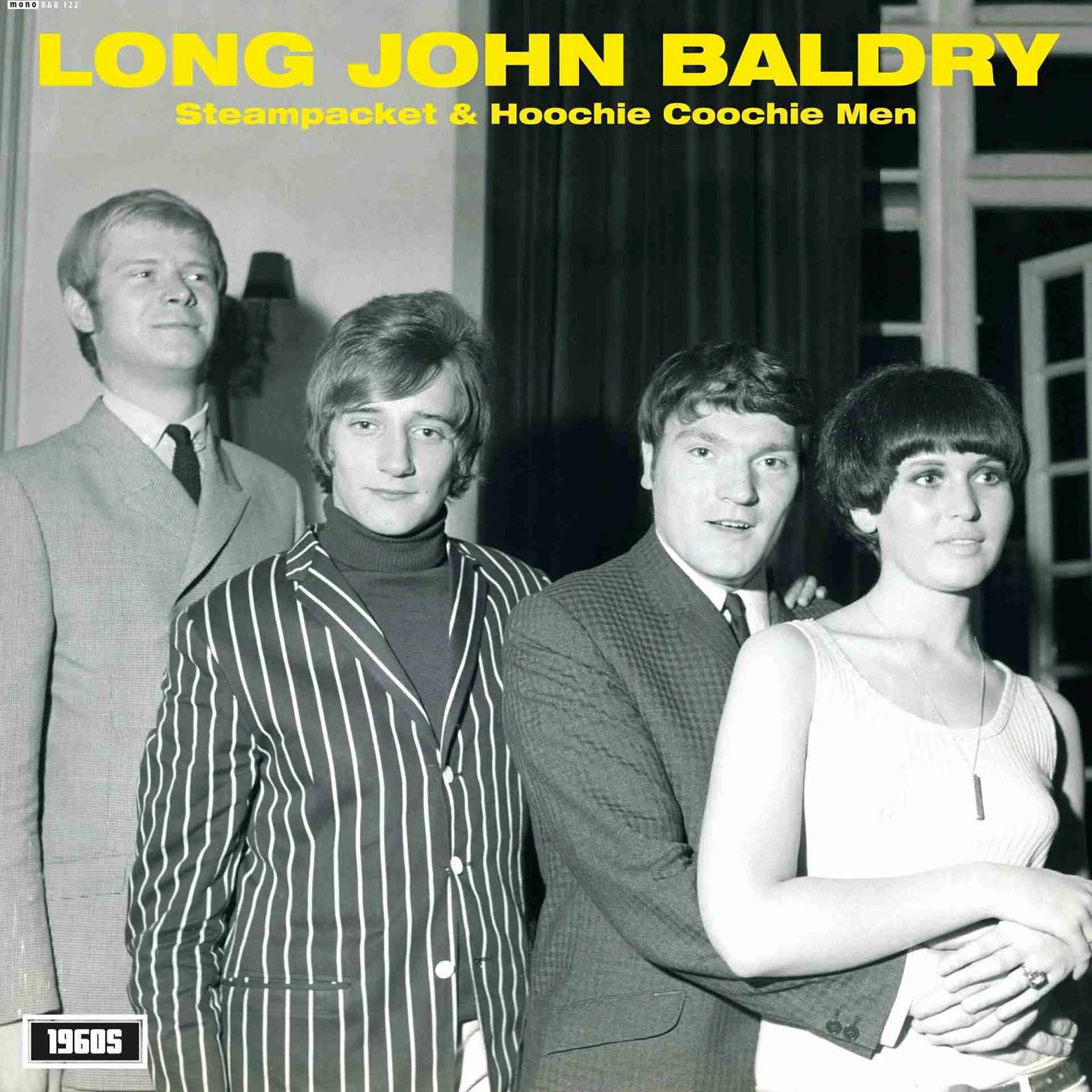

I called Long John Baldry, the man who discovered Rod in 1964, when travelling home from a residency on Eel Pie Island. “I lived in Hampstead,” Baldry said, “so I would catch the train from Twickenham to Richmond and then get the North London line which took me directly into Hampstead. I was on the railway station waiting for the Richmond connection. It was a very cold, foggy January the 7th, 1964 night, and I heard the sounds of Smokestack Lightning coming from the other end of the platform on a blues harmonica. That had a very famous riff - duh duh, duh-duh du-du du-du - and I thought, ‘Well that sounds pretty good, that sounds pretty authentic,’ so I went down the platform, saw a pile of coats with a nose coming out of the end of them, and I said, ‘Why don’t you come down and play some harmonica with us on Tuesday at the Eel Pie Island club?’ He said yes and came down, and it was a lot of fun and he stayed forever.”

Rod joined Baldry in the Hoochie Coochie Men, and his subsequent group, the Steampacket, playing the blues, mostly. “Rod was a very shy individual,” Baldry recalled. “He used to hide behind amplifiers on the stage. He was terrified of the audience. Of course, it’s completely the other story now.”

I asked Baldry whether Rod drank heavily before performances. He hesitated before answering. “I tend to think, knowing Rod as I do, that he wasn’t such a heavy drinker unless somebody else was buying.” He chuckled. “If it was on his own dime he didn’t drink so much. And of course he never smoked. From his wages, which I paid him, he was canny enough to save enough to buy a house. His only extravagance back then was clothes.”

Baldry said that the Rod of the mid-1960s looked very similar to the Rod of today. The hair was “more or less the same except a trifle longer, and instead of being cut into the spooky fashion it was backcombed with copious application of hairspray to hold it all in place.” The use of tartan as an accessory can be traced back to a tour date in Aberdeen. “I had no right to be wearing tartan because I have no Scottish roots at all, but we both bought Stewart tartan trews for our trip up to Scotland.”

Baldry noted that Rod did not seem ambitious. “Who was back then? We were all doing it for the fun of it and the fact that we occasionally got paid was a great bonus. The fun of it and a few beers during the evening - it was a very enviable lifestyle. Rod is a similar person to myself. We both share that eternal gypsy spirit.”

On the day of the cup final everything is a rush. When I arrive at Glasgow’s poshest hotel, I am shown to a lounge. The sounds of merriment can be heard leaking from the restaurant. The photographer, Drew, is waiting. At Rod’s insistence, he has entered the hotel through the windows of the dining room.

Much later, Rod arrives. He is tanned and well-watered, simultaneously smaller and louder than life. He wears a light pinstripe jacket and a dappled tie, loose at the neck, with light flannels and white shoes. His hair is tousled and streaked. His face is starting to dissolve. He is accompanied by a man he calls Doc. “My second father,” says Rod. “Or as close as you can get to it.” What I don’t know at the time, because the introductions are brisk, is that Doc is Dr Bob “Painless” Paterson, who gained his nickname while working as the Ayr United club doctor under the charismatic manager Ally “Tartan Army” MacLeod. Today, instead of giving painkilling injections to crocked knees, he is the responsible adult, administering the magic sponge to the interview process.

As time is short, I try to win Rod over by mentioning his extended family in my home town, North Berwick.

“They’re all bloody dead now, aren’t they?” Rod replies cheerfully.

“Dennis,” says Doc, reminding Rod of the owner of the town’s Nether Abbey, a drinking establishment favoured by lobster fanciers in the Royal Burgh’s west end.

“Dennis is still there, yeah,” Rod agrees, a little woozily. “Cousin long twice engaged. Cousin, yeah.”

“I’m going to have a big brandy,” says Doc.

“Me too,” says Rod. “I’ll be excited by that.”

I mention I have been speaking to Long John Baldry.

“No!” shouts Rod. “Bless ’im.” Rod confirms the story of the railway platform, and agrees that he was “far from” ambitious in those early years. “I wanted an excuse not to have to do a regular job,” Rod says. “It was either playing football, or singing. So I tried my hand at football. Well, that’s all history. You know all about that.”

The truth of Rod’s football career depends on which version the singer decides to tell. In his 2012 autobiography, he downplays previous claims of being an apprentice at Brentford FC. “I no more signed with Brentford than Gordon Ramsay played for Rangers,” he writes. Which is to say, he didn’t. But that doesn’t mean his love of the beautiful game is any less intense.

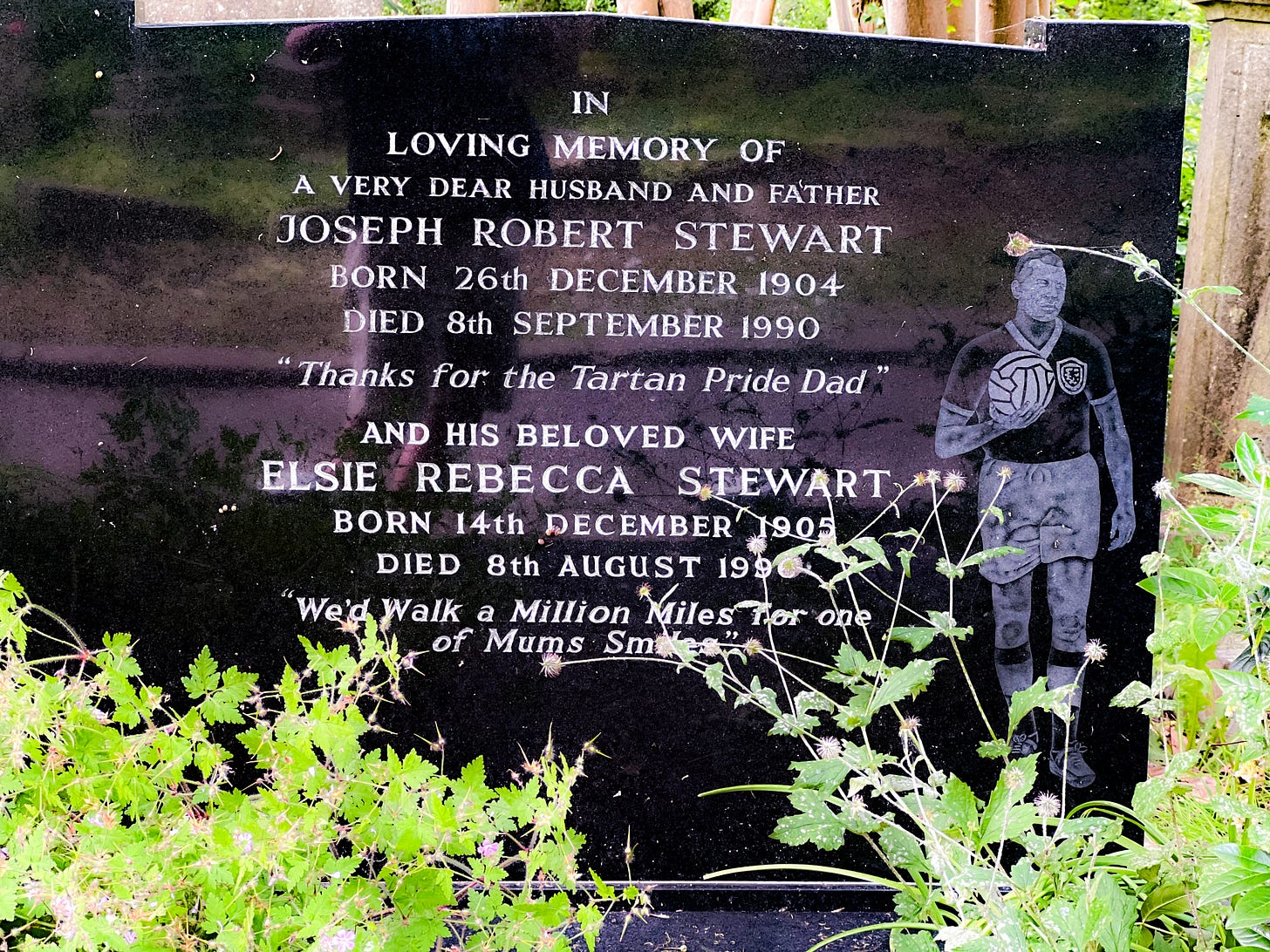

“The attraction of football - I’m very drunk, you’ll have to excuse me - is I grew up among a family of footballers. My big brother. My two big brothers. They played football. Dad was a great footballer. He was a Scot in the family and he put among us that Scottish football was the greatest in the world. We grew up with pictures of Eric Caldow and Bobby Evans, all those players. So he was a big influence on us. And it’s survived. He died three years ago.”

Rod is a purist of the old school. He likes to see clean football, with wingers. Is coming home a way of keeping in touch with things?

“I wouldn’t say coming back to Glasgow. It’s coming back to Great Britain. I like to keep in touch with football in Britain. And the reason we’re up here today - the team I play for in Los Angeles, called the Exiles, have sworn by Scottish football. Hopefully you’re going to see a great game today. I fucking hope it’s going to be a good game. Better be a good game.”

Rod’s devotion to playing football has not dimmed, despite a few injuries. His advancing years are pushing him further back on the field, from attack to defence. There is talk that his skills have been diminished by arthritis.

“No, no,” Rod says. “I had a cartilage problem. You operate on it, Doc. These are two of the guys who play on the team. Nathan over there, and this guy here - he used to play for the Greek national team. They just qualified for the World Cup. First team to qualify. SO HERE’S TO GREECE QUALIFYING FOR THE WORLD CUP!”

We talk for a while about Rod’s recent records. There are two. Both seem designed to prompt a re-evaluation of his talent. Rod is oddly dismissive of the MTV Unplugged album (“a collector’s piece, really”) preferring to talk about Rod Stewart: Lead Vocalist, a grab bag which adds a few new recordings, produced by Trevor Horn, to archive cuts from the Jeff Beck Group and the Faces. The five new tracks are cover versions. “This is the best vocals I’ve delivered in a long time,” Rod says.

I suggest to Rod that his talent has long been overshadowed by his image.

“Oh, absolutely,” he says. “I indulged it as well. I absolutely enjoyed it. I believed everything I read about myself in those days, in the period between say, 1978, ’79/’80 to ’81, I believed everything. And I agree with every critic, especially the guy from Rolling Stone that said I betrayed my talent and copped out. He’s absolutely right.”

Does it worry you?

“Nothing worries me. Nothing worries me. Nothing worries me at all.”

We talk a little more about music. Rod suggests that he still feels he has “the masterpiece album” in him. His voice, he says, is “fucking great, I tell you. I’m so proud of it. You listen to the MTV Unplugged album. The voice is so rich and big - it’s as good as it’s ever gonna get now, I think. I even shock myself sometimes.”

He is marginally less ebullient on the question of songwriting, admitting that his ego had taken “a bit of a bashing” when his last three hits came from cover versions. “I thought, fuck, I can’t write songs any more. Course you can write songs - if it’s in you it’s in you. You just need to rest from it, take a little step back, look at what’s happening in your life, and hopefully write about it. Would you like a drink now? You’re really fucking boring. You know that, don’t you?”

“I try,” I say, “but cheers.”

“Nah, I suppose you’re not going to the game. I wish I was going to an England-Scotland match. I really miss those games. I miss ’em. The atmosphere.”

It’s just about notable that Rod has reverted to football talk as an escape from introspection, but it’s also true that the mood in the room mitigates against thoughtful reflection. We talk for a while about music, and Rod says he is “still moved” by Sam Cooke, Muddy Waters and Otis Redding. He just about concedes that singing Da Ya Think I’m Sexy can be tiresome, before adding that the song was not autobiographical. “It was in the third person. I was the voyeur, if you want, looking at these other two people. So it wasn’t about me. It was supposed to be called Da Ya Think They’re Sexy, but my manager at the time decided to call it Da Ya Think I’m Sexy.” And Hot Legs? “There was nothing wrong with that. It was a rock and roll song and it was a rock and roll video. I still love singing that song.”

I suggest to Rod that many of his early songs are about people dreaming, and there is also an element of autobiography. “I’ve worked between those two spheres, really,” Rod replies. “The autobiographical and the running away.”

I ask whether the boy that Long John Baldry saw on the station platform could have foreseen where he would end up.

“Not in a million years,” Rod says. “I must admit when I first started singing, the first thing that was on my mind was not to become wealthy. It’s the typical rock and roll story, really. I wasn’t great at school, I was only good at playing football and singing. Those were the two things, and I wanted to show everybody else I could do something really well. I wanted to show me dad I could do something really well ’cause he had big, high hopes for me as a footballer, as he did for all three of his sons. I was the one who came closest to being a professional. When that all fell through he never wavered, he said if you’re not going to do football, I’m right behind you with the business. In other words, if you’re happy with what you’re doing, I’m happy. Which I admired him for, bless him, I wish he was here today. And he gave me so much support. The family gave me so much support. These two brothers of mine, they used to lend me twenty quid, thirty quid, brilliant. That’s why I do this for them now - fly ‘em all round the world to watch football matches - it’s my way of paying ’em back. Would you like a drink now?”

Rod pours another brandy. I suggest to him that his existence is almost royal. “Yeah it is,” he says, regally. “It’s wonderful, believe you me. I never want it to go back the other way. I quite enjoy being famous, and I enjoy being wealthy. If you’re a public figure, you’ve got to enjoy being in the public. If you don’t, then fuck off! Leave it to somebody else. There’s plenty of people trying to be famous. I enjoy every minute of it.”

We talk for a moment about Rod’s father, Bob. Though Rod was born in Highgate, North London, his dad gave him his strong sense of Scottishness.

“Doc,” asks Rod, “how old was dad when he moved down to England? Sixteen, 17?”

“Yeah,” says Doc, “he spent a spell in the merchant navy, didn’t he?”

“Yeah,” says Rod, “how old was he when he moved to London?”

“I would say early twenties,” says Doc. “No more.”

“Early twenties.”

“He was born in Leith,” says Doc. “During the war he was up in Monkton, Ayrshire.”

“You never fail to find out more things about your dad,” says Rod. “I never knew that.”

“Funny enough,” says one of Rod’s brothers - whether it’s Don or Bob is hard to say - “Gordon Strachan, who I know quite well, and Rod knows quite well, his grandmother went to the same school, probably at the same time as my dad.”

“If they’d have shagged each other, we’d have a footballer,” says Rod, delicately.

“As Rod said,” says Rod’s brother, “with a little bit of eh … he could have been his uncle’s auntie’s sort of…”

“How’s your father?” says Rod.

Time is wearing on. Kick off is in 45 minutes, on the other side of Glasgow. The photo is still to be taken. “We’ve just gotta go and put our make-up on,” says Rod. Rod, his brothers, and most of the LA Exiles football team disappear into the powder room. The muffled sounds of bawdy songs can be heard. Moments later, the door bursts open, and Rod leads the gathering in a conga line through the lounge into a hallway. Rod has a laundry basket on his head. “Just one with the basket, for me,” Rod says to Drew, the photographer.

“Quick, Rod, honestly, we’re gonna miss the kick off,” someone says.

“We never see the kick off and we never see the end,” says Rod.

“Has anyone seen my face?” says Rod’s brother Don, as the laundry basket is placed over his head.

“What do they do at the kick off?” says the other brother, Bob. “Do they throw the ball up in the air?”

“Actually there’s a coin involved,” says a third voice.

Rod, his brothers, and the laundry basket are now posing for a portrait.

“That’s good with the background,” says someone encouragingly. “Sultry look, Sultry look.”

“Take your trousers down,” says someone else.

A riotous chorus of the traditional Scottish song A Gordon For Me breaks out. “Gordon for me, gordon for me, if you’re nae a Gordon then you’re nae use to me.” The photo shoot is over, 90 seconds after it began.

We clamber onto the bus. I am seated up the back near Rod. A radio is turned on for a pre-match report. The radio suggests that Aberdeen manager Willie Miller will have to guess whether Rangers manager Walter Smith will play Gary McSwegan in a withdrawn role to support Mark Hateley. Eoin Jess is not fit to start, but may be on the bench, but Aberdeen have a problem at left back. The radio drones on. A chant of “Aberdeen, Aberdeen” fills the bus, quickly mutating into a chorus of Here We Are Again, Jolly Good Company. “Never mind the weather, never mind the rain, now that we’re together, off we go again.”

“Keep the cans down lads, keep the cans down,” shouts someone from the front of the bus. “Keep ‘em down, keep ‘em down, keep em down,” goes the chant.

“Keep the fucking cans down,” the voice repeats, and the chanting mutates into a chorus of “A wee bit of sugar makes the Venables go down.” (Two weeks earlier, Tottenham Hotspur chairman Alan Sugar had fired Spurs’ manager Terry Venables).

Drew takes a picture.

“No more pictures,” says Rod.

The tickets are divvied out, along with the passes for the Jock Stein Suite.

“What’s the next question?” Rod shouts.

What about the rumours that you’ve settled down, I say.

“What does it look like?” Rod says. “I’m a Jekyll and Hyde. I enjoy a couple of days out with the boys and I enjoy being a family man.”

I have to shout to be heard now. “Do you live primarily in LA?” I ask.

“Yes.”

“What’s it like?”

“What would you think?”

“I would imagine you don’t live in South Central.”

“No, I try to avoid that area as much as I can.”

Who are your neighbours?

“No one. I’ve just built a new house. I don’t know who my neighbours are.”

“What’s it like?"

“What’s this got to do with music?” Rod says.

I suggest to Rod that he might try and recapture some of the magic of his early records by reuniting with the musicians. He looks baffled, and says he can’t, because most of them are dead. We go round in circles for a while, with Rod also ruling out a reunion of the Faces. “The only reason we’d get the Faces together would be to raise money for Ronnie Lane. I don’t think the world needs a Faces reunion. I think there’s enough good bands around.” He rules out playing in smaller venues, because he would disappoint so many of his fans. I realise that I am now getting into George Best territory, asking Rod why he doesn’t do the things he did when he was much less successful.

Another song erupts on the bus. It is Irving Berlin’s When I Leave The World Behind, which tells the story of a millionaire who is “burdened down with care” and thinking of his will. The singing is riotous now.

I leave the sunshine to the flowers

I leave the springtime to the birds

And to the old folks I leave a memory of a baby on their knee

I leave the night time to the dreamers

I leave the songbird to the blind

I leave the moon above to those in love

When I leave the world behind.

“TA TA TA TA TA TA TA TA TA!” Rod shouts, impersonating a snare drum

“When I leave the world behind.” The song collapses into drunken cheering.

“I like how we broke into that, impwontu,” says Rod.

“Impromptu,” says someone

“Impwomtu,” says Rod, as the chorus now switches to Me and My Shadow, with vocalised jazz drumming.

When it’s 12 o’clock we climb the stairs

SHOOBIE DOOBIE TATTEDY DEE

We never knock - WHY? There’s nobody there, just me

TA TA TA TA TA!

The Doc interrupts, pointing out of the bus window at the Royal Infirmary.

“We could all get in there and get treated!” he says. “I remember when I studied there, by Christ, aye! There’s the gate there.”

“Who did you shag in there, Doc?!” shouts someone (not Rod).

“I’ll tell you a story,” shouts Doc. “A true story! I was at the gate there, right? Saving lives all over the fuckin’ place. And a guy comes down wi’ a big slice doon his face. And I said, ‘Holy Jesus Christ. I’ll try and stitch that for you. So, he’s put in a wee cubicle, this cunt. I had three other cubicles going at the same time, you know? And I run in and look at this - it’s a lovely straight-cut razor. I said ‘No problem here, 25 stitches and we’re off’. So I start, and I’m turning and planing away and suddenly four guys walk in and say: ‘What are you fucking shouting about?’ This cunt was screaming off his head, and because he was drunk, I didn’t put much local on, you see, so I’m knitting away and these cunts walk in. “HEY!” I think, ‘Oh fuck, this is me done, they’re gonna do me.’ I says to the guy sitting in the chair ‘Shut your mouth! The doctor’s trying to help ye.’ So I keep on stitching. And I finish up, and I say, ‘There you go, son.’ And this guy, the boss of the three of them walks over, hits me on the shoulder: ‘Great job! I’ll away and get you more customers, doc, OK?’”

Rod offers a steady handclap, perhaps signalling that he has heard the yarn before. “True story,” Rod says.

“That’s absolutely true,” Doc says, addressing me directly. “Absolutely true. When you’re in medicine, things happen. Forty years in medicine. Things happen you wouldnae believe. Another example. I got called in, 10 o' clock at night, the story was ‘I was bathing the baby in front of the fire, and I got burnt.’ I went up to this wee cottage, and here’s this baby, first look, I thought, no problem. Cos if you have a really badly burned baby, it looks as if somebody’s hit it with a hammer. And they’re in shock, you know? So this wee thing’s lying there, and I said, where’s the burn? So she turns the baby over, and points to a wee thing about the size of a needle. A wee red spot. That’s it. I go: ‘I don’t think there’s much to worry about here,’ and she says, ‘But what about the shock, doc?’ And I said, it’s quite all right, I’ve recovered.’’’

“Brilliant,” says Rod.

The bus is now on its way through the East End of Glasgow. Someone is whistling “here we go, here we go”.

“There’s the Barras,” says someone as we approach the famous market.

‘Trendy Fashions,” Rod exclaims, noticing a modestly boastful clothes shop. “Togs! Price War Fashions!”

“Dress yourself here, sneeze and you’re naked,” says someone.

“Oh, there’s the Barrowlands,” says Doc, “Christ! Barrowlands! I used to dance there to Billy MacGregor. Do you remember Billy MacGregor?” MacGregor and his band, The Gay Birds were the resident entertainers at the famous ballroom. “No, you’re too young. Fucking magic.”

“That looks like our type of place, Doc,” says Rod gazing at an intimidating looking bar.

“This is some area, this,” says Doc. “The Crystal Bells down there, too. You know the Crystal Bells? The only place I saw a razor flashed properly. Terrifying, man. You know an old razor? What they do is they flick it over. I was in there drinking with the boys that were the thrower-outs at the Empress Theatre and this cunt walks in, turns his glass upside down. That means he challenges the bar. He whips out this razor and goes like that. If you move, you’ve challenged him. And this big guy from the Empress, he walks over and just fucking fells him. That’s what he did. Everybody was out the pub like that, you know? People don’t think that happens in Glasgow. That happened to me. All the stories I tell you are true.”

“Operation Blade,” says Rod, referring to a knife safety campaign. “You hear about that a lot.”

One of Rod’s brother’s is enquiring about the possibility of a stop on the way to the stadium.

“Stop what?” says Doc.

“Well, there’s the public hoose,” says Rod’s brother, gesturing to a pub surrounded by Rangers fans. “Next round’s down to Doc Paterson.”

“I’ll pay for it,” says Doc. “I’ll pay for it all. Open the window and make an order.”

“Do you think I could do that?” asks Rod. “Just pull up on the wrong side of the road, and I’ll buy all the boys a drink.”

By now, the mess is threatening to get messier. Doc asks whether I come from Glasgow. No, I say, Edinburgh. “That’s a bit fucking awkward,” he says. “Leith?” says one of Rod’s brothers hopefully. I mention North Berwick. “You mean Dennis Stewart and the Nether Abbey and all that shit? I know them so well,” says Doc.

“And the Iona Hotel,” says Rod.

“The Iona,” says Doc. “And the Golf. The Castle at Dirleton. The Open Arms. And the Ship Inn. I know the Ship Inn. Nice place. I went to North Berwick 20 years in succession for my holidays.”

Rod starts to sing an old music hall verse about a girl “that married dear old dad.”

“She was a pearl, and the only girl, with eyes so blue, one who loved nobody else but you,” he croons. I try to ask Doc how he knows Rod, but his answer - something to do with a documentary that was broadcast at one on the morning and - perhaps unrelated to this - a Miss Iceland who became Miss World - is drowned out by a chorus of Gershwin’s Swanee, with Rod on lead vocals. “My mammy’s waiting, praying for me,” he sings, as the rest of the bus attempts a complicated harmony part. Strolling by Flanagan and Allen follows. “I don’t envy the rich in their automobiles,” Rod sings.

“He loves that line,” says one of Rod’s brothers. “He loves it.”

“For a motor car is phoney,” Rod continues, “I’d rather have Shanks’s pony.”

“Rod,” says Doc. “How many times have we fucking heard this?”

“Ratatatattatata,” says Rod, now moving into vocal percussion. “Shall we get out?”

We are almost at the stadium, and the vehicle has slowed to walking pace. An air of reminiscence has settled on the bus.

“My first job was a foundry boy, then I did metallurgy and then I did medicine,” says Doc as a chorus of “We won the fucking league, yes we did,” breaks out on the street.

The tickets are handed out, with strict instructions to attend the managers’ office after the game for a drink. “Three goals up at half-time and we’re off,” says Rod.

The doors open and the noise of the crowd rushes in as the LA Exiles, the Doc and Rod spill, almost literally, onto the street.

“There’s Rod Stewart,” a passing fan shouts to his mate. “He’ll get you a spare ticket.”

Years later, I interview Rod again, this time at a rehearsal studio in North London. It is a less ebullient affair, though it finds Rod’s reputation more in keeping with the times. The new man has been replaced by the lad, and rock and roll and terrace culture are aligned once again. Rod professes his admiration for Oasis. “I like the guy in Oasis,” he says. “He’s all mouth and trousers. I like that spunky, rebellious approach.” Rod also reveals that at the age of 50, he has installed a full-sized football pitch - “bigger than Ibrox” - at his Essex home and is hoping that Frank Lampard Sr, then the assistant manager of West Ham, will join him for training sessions.

I mention to Rod that he reminds me of George Best. “Yeah,” he replies. “He’s probably shagged some of the same women, if we were to compare notes.”

(Adapted from a chapter in the book, Alternatives To Valium: How Punk Rock Saved A Shy Boy’s Life) This entry may disappear behind a paywall at some point.

"Punks hated us because we weren't punk. Everybody else hated us because they thought we were."

In March 1994, I interviewed Jackie Leven. He was an under-appreciated figure then. He remains that now.

From Teddy Boy to Hitler To Christ

Alternatives To Valium is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

My guy! https://open.substack.com/pub/lorichristian/p/rod-stewart?r=4fd1oa&utm_medium=ios

Remember enjoying this in the book of the same name! Great Rod story. There was an interview with him in the recent edition of AARP. (The mag for old people in the US.) He's 80 now, and though he says he can't remember when he was last drunk, his lust for life - or at least his joie de vivre - remains unbowed. Lovely piece.