Yesterday, February 4, was the anniversary of Alex Harvey’s death in 1982. Today, February 5, would have been his 90th birthday. This is a celebration, drawn from interviews I did with the Sensational Alex Harvey Band. Be warned, there are swear words.

A few years ago, during the tedium of an airport stopover, Nick Cave got into a text exchange with Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream. The two singers were texting about Alex Harvey, the front man of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band. To alleviate Cave’s boredom, Gillespie sent links to YouTube clips of SAHB performances. Cave confessed that his first band was essentially an Alex Harvey tribute; they played Framed, Isobel Goudie, Faith Healer, Gang Bang, Next, Midnight Moses. Cave said he wore a tight, cropped T-shirt, and the guitarist had clown make-up, like SAHB’s Zal Cleminson. The text exchange ebbed, then Cave offered a brisk summary of Harvey’s gift. “Such fucking venom,” he wrote.

In another room, on a less malefic occasion, I had mentioned Harvey to Cave. Cave was aggressively reticent, but - freed from the obligation to talk about himself - suddenly sprang to life. “Alex Harvey was where it was at, man,” he said. “Living in Australia as a kid I never knew what a fucking Scotsman was, let alone had I heard one. And his lyrics, which are just the most twisted thing … the places he went, nobody went.”

If you know Alex Harvey, it isn’t surprising that Nick fucking Cave was influenced by him. Imagine a theatrical performer constructed from synonyms of venom. Bitterness, hatred, rancour, toxicity, acrimony, anger, contagion, infection, malevolence. Imagine Alex Harvey singing Nick Cave’s Red Right Hand, or The Weeping Song. Now try Nick Cave singing Harvey’s Hammer Song. As chasms go, it’s a small ditch.

Rat Scabies, the drummer of The Damned, is another malchik who testifies to Harvey’s influence on punk. Alex was, Scabies told me, one of “the people that really understood what was going on. I remember reading a big feature with him in Melody Maker, with Gary Holton (of Heavy Metal Kids) and some other loser. They was talking about the trouble with our youth and football violence, all of that, and where’s it going? Alex Harvey was just so on the money, even though he was the same age as most of our audience’s dads.

“There’s a great video of him on YouTube. He starts a song off in a grubby old Mac and a flat cap. It's acting, it’s theatre. But by the end of the song, that’s come off, and he’s got the leather jacket on, and his hair’s combed back into a quiff and he’s become a totally different person. I haven’t seen anybody - a singer in a band - do anything like that. For me, Killing Joke stole everything off them. They wanted to be the Alex Harvey Band.”

Here, as we tiptoe a little closer to the fire, is the Sensational Alex Harvey Band’s guitarist SAHB Zal Cleminson talking about the singer’s pre-gig ritual. The band, he suggested, would be like gladiators preparing to enter the arena. Alex had a full routine. “Standing on his head. Getting breath control, doing front curls and stomach curls, abdominal isolations, and breathing exercises. Then he would just stand and stare into the mirror and start shouting: ‘Cunts! Cunts! Cunts!’”

It was, SAHB bassist Chris Glen told me, like Travis Bickle confronting his reflection in Taxi Driver. “He’d look in the mirror and go ‘Cunts! Cunts! CUNTS! And keep going.

“Other bands do humming and singing exercises,” Chris said. “That was Alex’s way of getting himself psyched up.”

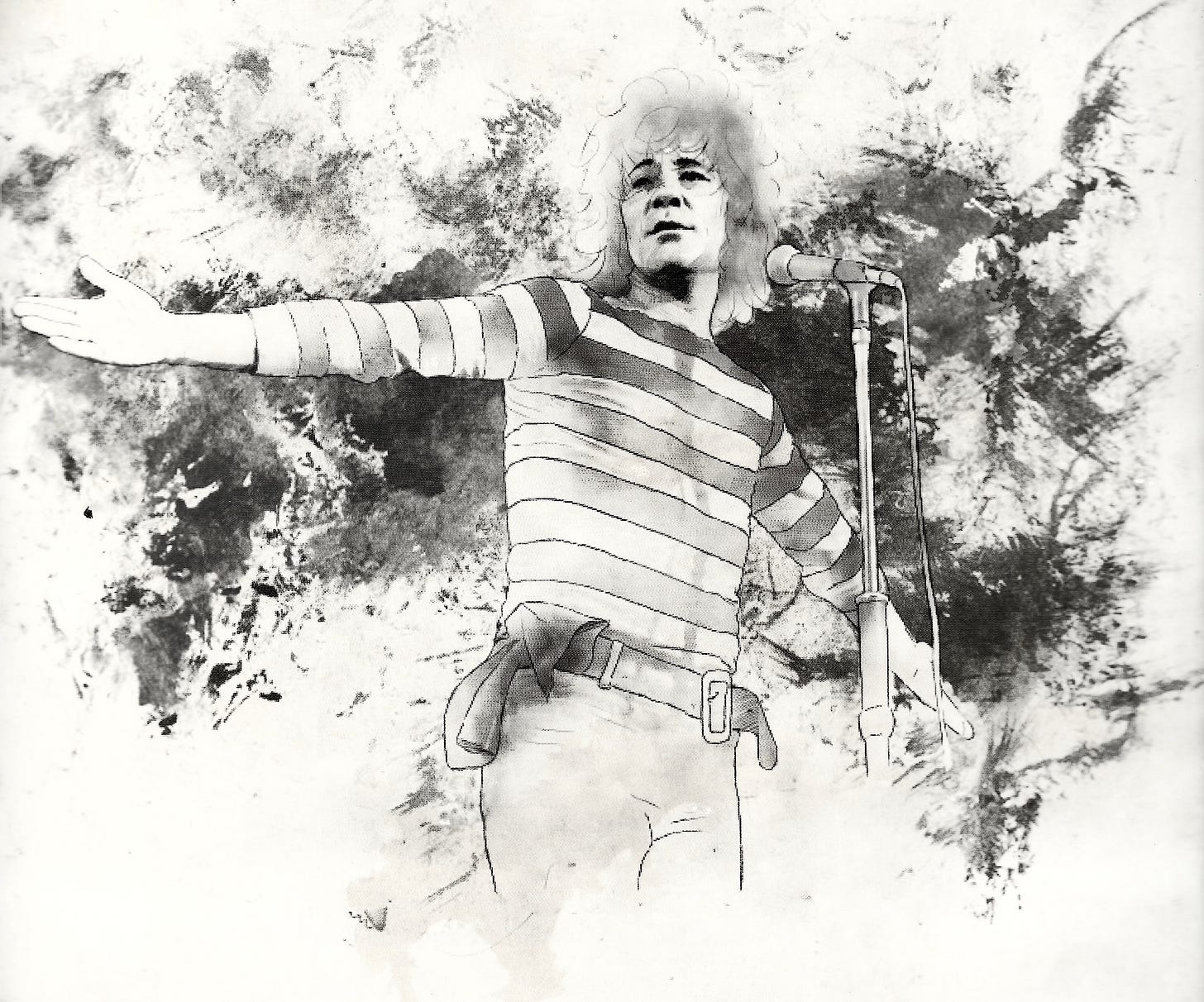

It is one of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band’s great misfortunes that they existed in the years before MTV. They would have suited the video age. As it was, their power was best understood in concert, where Harvey’s command of an audience was total. SAHB keyboard player Hugh McKenna explained to me that Alex’s theatricality was rooted in the songs.

“He did act them out more than sing them,” Hugh said. “He didn’t have a beautiful voice, but he had a very distinctive voice. It cut through. It was quite a chilling voice sometimes. It would freeze your blood, some of the noises he made.

“There were similarities between him and Ian Dury. They knew each other quite well. Ian Dury, like Alex, had quite a roughneck persona. He was also older, like Alex.”

Generally, SAHB shows would peak during Harvey’s assault on Framed, a Lieber and Stoller song that wore its politics lightly when first performed by The Robins in 1954. Harvey’s career ran pretty much in parallel to that song, which became a standard, with notable versions by Bill Haley and Ritchie Valens, later finding favour with Los Lobos and Cheech and Chong. Harvey’s path was similarly jagged, winding from skiffle to beat to soul, before the full ripening of SAHB, and - in the face of punk - retreat and collapse. It is the rock’n’roll years in miniature.

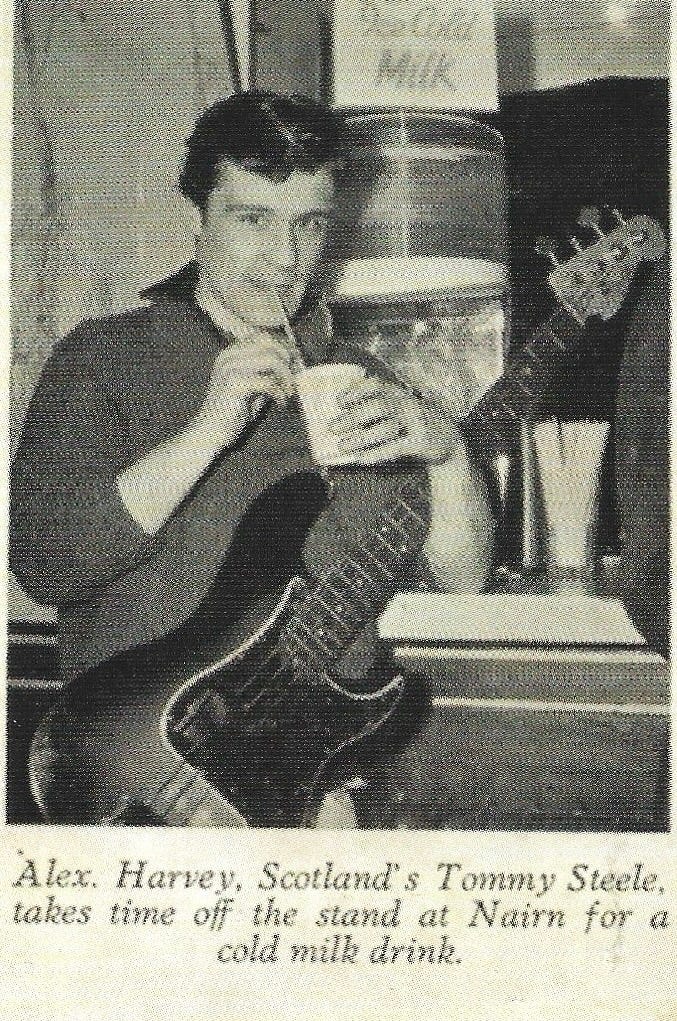

Harvey's first breakthrough was in the 1950s, when he won a competition to be crowned “Scotland’s Tommy Steele”. (Steele, in almost the same breath, was referred to as “England’s Elvis Presley”). In 1960, Harvey shared a bill with The Silver Beetles on a Scottish tour, when John Lennon (Johnny Lennon), Paul McCartney (Paul Ramon), George Harrison (Carl Harrison), Stuart Sutcliffe (Stuart de Staël”) and drummer Tommy Moore were backing Johnny Gentle. Harvey’s early 1960s revue group The Big Soul Band, included Framed in its repertoire. They were, said SAHB’s guitarist Zal Cleminson, “an outfit that was very well rehearsed and full of good musicians. They played more like an American band, with a kind of James Brown approach.” (One curiosity of the Soul Band was a line-up with two bass players, a quirk they shared with Dean Ford and the Gaylords, who became Marmalade). “They did a lot of soul,” said SAHB drummer, Ted McKenna, Tamla Motown sort of stuff, and a lot of that was based on riffs.”

SAHB itself was a hybrid, a merger between Harvey’s charisma and experience, and the power of the band, who started out as the more progressive Tear Gas.

“The first time I met him was when he appeared in the Burns Howff, an old pub that ain’t there anymore,” said Zal. “He came sauntering in with his guitar case over his shoulder, sat down, bought us all a drink, and he filled in a few details about what we were trying to do. We were a little bit sceptical. We were younger than him and we were all a bit cocky. We thought we were the next Led Zeppelin. He was quite laid back about it all. We had booked a little rehearsal room up the road – Bath Street somewhere. He played us the riff for Midnight Moses, and he was asking us, ‘How would you play that?’ So we just battered it about, and I could see on his face, this grin coming over him. He was bouncing about on his brothel creeper shoes. It was quite a magnetic moment.”

So, Framed. One of the few YouTube clips of SAHB shows a 1974 performance at Ragnarock, a festival in Holmenkollen, Oslo. The clip shows Harvey in complete control of the stage. He puts on his leather jacket and smooths his hair back with beer. He stands with his arms outstretched, as if being crucified. He licks a pair of nylon tights, before stuffing them into his cheeks. Finally, he pulls the tights over his head like a bank robber, singing all the while about his innocence.

SAHB’s drummer, Ted McKenna, told me about an even more incendiary performance of the song. “Alex went on as Hitler in Berlin. We said ‘Alex, please don’t do it’. But he did it. All the German kids were swaying, and Alex just loved it all. He thought it was crazy. He went on with a gaffer-taped Hitler moustache. He brushed his hair to one side and had a swastika on his leather jacket. He also went on as Christ at Reading, and sang the same song – ‘I didn’t do nothing, I was framed.’ There’s your story right there, from Teddy Boy to Hitler to Christ. All in the same stage performance.”

The roots of that stage performance went deep. Harvey played in the stage band for the musical Hair, which shook up London’s west end in 1968, bringing drug-taking, anti-war sentiment, and brisk nudity to Shaftesbury Avenue, along with chants of “beads, flowers, freedom, and happiness”.

“Alex was in Hair for a good many years,” said his widow, Trudy. “I think the fact that he had been in amongst people on stage meant he started to think a little theatrically.”

Alex and Trudy lived in Hampstead in a house with seven musicians. There were, she recalls, many comings and goings. One visitor to the house was another rock musician who was playing around with theatrical presentation: David Bowie.

“David had had some success with music,” Trudy said, “but he was an unknown, and he used to come and sit on the floor with us. He came to see me when I was in hospital and had my son. At that time he was playing songs on stage with the mime artist Lindsay Kemp. He just stood on the side of the stage and did his songs, and Lindsay Kemp did his thing. Lindsay must have been an incredible influence on David. Not long after that Alex and I were in Glasgow, and David suddenly became famous. We went to the Apollo to see him. We watched his show. We thought we would go and say hi, but we couldn’t get backstage, because it was teeming with teenagers. That was the last we had anything to do with him.”

Ted McKenna recalled Alex and Bowie going UFO spotting on Hampstead Heath. “It’s true enough,” said Trudy. “They talked a lot about space. I think Alex recommended that David read Arthur C Clarke’s Childhood’s End. So yes, it was absolutely that atmosphere of … flying saucers. It was in the middle of the hippie era.

“There used to be a newspaper called International Times. And there was something in it that said ‘Come to Hampstead Heath to join Yoko Ono, and learn how to catch’ … wait for it - ‘an imaginary butterfly’. That was the era. I can’t remember if we caught any butterflies. To my recall we didn’t. But I think someone was handing out sardines in tins. Sort of feeding the 5000 or something. Yoko Ono wasn’t even known then. It sounds so crazy when I think about it now.”

“I used to go up and visit Alex and Trudy quite a lot and stay the night,” said Hugh McKenna. “He’d play me lots of stuff. He was into Louis Prima. He used to point out things in the music, like he’d listen to what the bass was doing and he’d mimic it, and analyse what made it swing.

“Alex was much more direct in his approach to music. He wasn’t into a lot of flowery stuff. He liked to strip things down musically and take away stuff that was superfluous and make it very pointed and direct.

“He was very eclectic in his tastes. The first time I ever heard Luciano Pavarotti was at Alex’s house. Alex had a recording of Pavarotti doing La Boheme, and I was just blethering away, and Alex said ‘he’s the best tenor in the world, it’s just that people don’t know it yet.’ And he used to play Moroccan folk music and stuff, Indian music.

“The theatricality of the band was a joint thing. Zal pulled so many faces when he was playing the guitar and he wanted to find some way of emphasising it. Then Alex and a couple of the boys went to see Lindsay Kemp, and they got the idea for the white face from that.”

“We were all heavy and serious and interested in looking at our feet while we were playing,” said SAHB bassist Chris Glen, “and we were absolute monsters offstage. Alex turned it completely around. He said: why don’t you use the egos you have offstage and apply that onstage?

“Every band used to wear jeans and leather jackets back then. His idea was: wear what the fuck you want – exaggerate your own personalities so that nobody in the band looks the same. You all appear to a different section of the audience. We never did anything for image – you had to feel comfortable with it.

“It was a blessing and a curse. We sold as many albums as people we played to. But if you bought an album, it would sound like a compilation album. There was a bit of jazz, a bit of tango, a bit of fuckin’ this and that. But go and see the show and it all makes complete sense.”

Snakes, serpents, jellyfish, deathstalkers. So much for venom. But what was Alex Harvey like? “He liked the idea, Alex, of being a father figure,” said Zal. “A lot of people who saw Alex performing, and offstage, would have got the impression that he was a madman – not in a lunatic sense, more in an angry sense. He seemed to be angry at a lot of things. That was borne out of his experience of his brother Leslie (who played with Stone The Crows) dying on stage when he was electrocuted. He carried that around with him a little bit. He had a social conscience as well. Even in the lyrics of the songs he was trying to get across this message of ‘don’t piss in the water supply’. These were the very early days of people saying we should look after the environment.

“I recently watched a programme about Christianity, and Jesus carrying a sword. It’s the same idea, of someone with a peaceful message who, if it came to the crunch, was prepared. I’m not comparing Alex to Jesus, but he was in the same mould. Although he was a pacifist. He was a conscientious objector - I think he had to go to court – and his father before him was a conscientious objector.

“That was just a legacy of being brought up in the Gorbals. You had to look after yourself. And obviously hanging out with people who were prepared to do this, that and the next thing, like we all did in Glasgow. You can make a choice about how to avoid that sort of thing and how to get embroiled in it, and he had a bit of both.”

Ted McKenna recalled the first time he saw Alex turning his confrontational urges onto the crowd. Alex was at a show above the Apollo to watch his brother in Stone the Crows, and joined Tear Gas for a few songs, before doing some acoustic numbers on his own. “My heart sank, because these people were all booing and he was going ‘Ya fuckin’ bunch of cunts’. He was just getting tore right into them, telling them they were a bunch of idiots. I didn’t know what to make of this, but I realised later on that it was the essence of what we did, and what Alex did. He made sure that people wouldn’t take him lightly. He always used to say: ‘They won’t forget us’. Because his whole raison d’être when he went on that stage was to be sensational, to make sure that he got them. You liked it or you hated it, and that tends to be the equation for success.”

It wasn’t entirely a persona. “I once saw him put the head on a guy,” Hugh said. “At the Speakeasy. Alex bumped into this guy when he was dancing with Trudy, and the guy was drunk. He was an idiot and he took offence, and he tried to kick Alex. Alex moved out of the way and he tried to kick him again, and Alex just grabbed him by the lapels and nutted him and laid him out on the floor. Knocked the guy out. The guy asked for it. But it just showed that Alex could, if necessary, hit someone. Though I never saw him hit anybody else.

“He could be intimidating mentally … psychologically when he wanted to be. He would assume his magical persona. He’d read a bit about hypnosis and various things, he was very strong mentally. He had a powerful persona. He could intimidate people by looking at them. He had very dark eyes, like a gypsy. Almost black eyes. He’d give you a look that would just chill you. And he could speak in a very menacing voice. He could put the wind up you. And did sometimes.

“There were times when I was psychologically a bit wary of him. On the other hand, a lot of the time he was very good company, and he could be a great laugh. He was a very good storyteller. He was full of repartee. When he was in a good mood he was really good company. And more often than not he was in a good mood. He wasn’t inclined to be nasty very often.”

Alex was a keen reader of comics, and invented a mythology around the character of Vambo, a kind of Gorbals glam superhero. “Maybe it was the rags to riches story,” Hugh said, “though, God knows we never got any riches. But the story of the boy from the Gorbals who became a pop star. Maybe he played that up, and why not? Because of where he came from, he wanted to invent the character of the superhero who understood the kids. He felt that he understood troubled kids, troubled teenagers. And I think he did.

“I think it was because of people he knew when he was growing up who became criminals. He’d seen how you could go that way coming from his background.”

“He was driven to have a message,” Ted said. “He did want to tell people: look after yourself, look after your world, don’t piss in the water supply. Don’t buy any bullets, make any bullets or fire any bullets. He wanted to be a messenger of something new. He was a kind of revolutionary.”

The riches, as Hugh attests, never arrived. SAHB were a popular live band, but their career was, they all agreed, hampered when they scored a hit with a cover of Delilah. “Our management were desperate for us to have a hit single,” Ted said. “‘Get the single, guys, then you can do what you want’. No, you can’t! Once you’ve put your head above the parapet, people say ‘give us more of that.’ In fact, when we went to number 7, we got a telegram from the guys that wrote Delilah saying they had a few more if we were interested. It ceased to be the band and became the usual free for all for songwriters. It’s easy to see that in retrospect. We didn’t have any choice in it. We were in America when it was released. They released it without our knowledge. It was just a song that went down really well, and the only reason we did it was so we had another song - since we dropped Runaway - to do a silly dance in.”

There was one more hit, with Boston Tea Party, but the coming of punk with its emphasis on youth made Alex look like a man from another time, even though he was urging SAHB to sharpen their attack. He was also disillusioned and depressed, and strongly affected by the death of Elvis. “You’ve got to remember,” said Zal, “Elvis was one of Alex’s heroes. I don’t mean he was in awe of him, but he had massive respect for him. The fact that Elvis died, I think that brought Alex’s mortality to himself. Ask anyone what Alex’s reaction was to Elvis’s death, and they’ll all tell you the same thing: a variation on the word ‘devastated’.”

“We came back from the second last gig we ever did,” Ted said. “We were playing with Thin Lizzy outside Brussels, and when we came back, he wanted us to go to the Vortex, the punk club in London. This was 1977. He wanted us to go down there, with the pipers, and go down and play in a punk club to all these young kids that were spitting, and he would go ‘Right sonny boy, here’s the way it goes, boys and girls.’ He was going to get right into them. He knew the wave that was happening. He really understood what was going on. The club was run by one of our ex-tour managers, John Miller, who kidnapped Ronnie Biggs. So Alex said ‘We’ve got to go down there.’ But I’d just met my kid’s mother, and I said, ‘no I don’t really want to go out to a nightclub tonight.’ I don’t think anybody went down with Alex. But he got up with the pipers in this punk club, and all the kids were spitting at him.”

SAHB dissolved in acrimony, and Alex continued, to ever decreasing audiences, until his death in 1982, at the age of 46. “He wanted to change,” Trudy said. “He wanted to do something different. For all his fame, he never made very much money. I think it got to him. In the process, he’d lost his brother. He lost his manager in a plane crash. He tried to do something different.”

In the end, it comes back to Framed. Zal recalled another notable performance of the song, this time at the Glasgow Apollo. “I think we were the first band to sell it out for three nights. On one of the nights were doing Framed. At the end of it, the band stop and Alex goes, ‘I didn’t do nothing, I didn’t do nothing’. You’ve got 3500 people in the Apollo and you can hear a pin drop. And Alex is going ‘I didn’t do nothin’.’ And right from the back of the hall, someone shouts out, ‘You shagged my sister in 1974’. The whole fuckin’ place collapsed. Alex just burst out laughing. He said ‘Right, that’s it, concert’s cancelled.’”

These interviews were carried out over three separate occasions. Alex Harvey died in 1982. Ted McKenna and Hugh McKenna both died in 2019. Zal Cleminson and Chris Glen are still active in music.

I absolutely love this piece! I played in a semi pro band on what I now call the Average White Band circuit, gigging in pubs and dancehalls all the way up the east coast from Dundee to Fraserburgh, and we played quite a few SAHB songs in our set.

I also remember an interview in the Melody Maker where Alex was talking about Robert Louis Stephenson and his use of language, but in the same interview, he also talked about the ethics of living in a commune, saying, “you’ve got to remember that somebody has to wash the dishes”.

What a fabulous complicated man he was. Thanks again.

Thanks for this great and illuminating portrait. SAHB had a lot of supporters among our readers of Sounds 1971-4 — and the staff too! Do I remember right there was a live album recorded at the Marquee. Or maybe it was the Star Club, Hamburg? I wish I still had it.