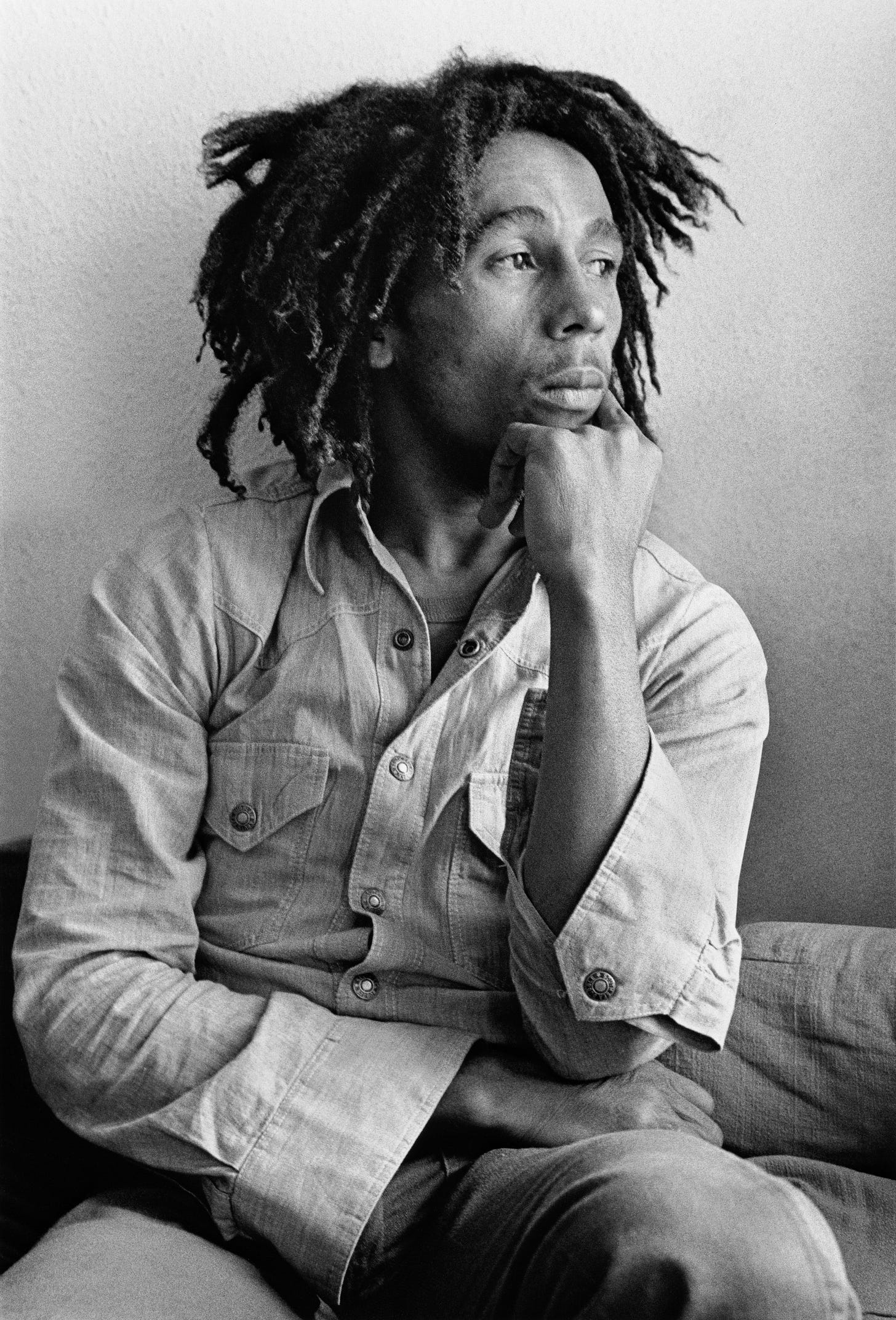

Unmasking the Public Image: The Rebellious Moments of Punky Reggae Photographer Dennis Morris

The Hackney photographer bunked off school to follow Bob Marley and everything changed

Dennis Morris took many pictures of Bob Marley. One of the most striking is the shot he took of Marley looking back from the front seat of a Transit van as the Wailers - a line-up including Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer - set out on their tour of England in November 1973. Morris had bunked off school to document the tour, and the picture captures a note of paternal concern beneath Marley’s easy charisma.

“He’s looking back at me and he’s saying ‘Are you ready, Dennis?’ Morris recalls. “And then the adventure began.”

The tour took the Wailers to mainstream venues, as part of Island boss Chris Blackwell’s plan to introduce reggae to a rock audience. Marley was philosophical about the sparse attendances, reasoning that a crowd of 200 could grow into one of 400, then 600. The other Wailers were less convinced, and were horrified by the British diet. Ital food was not available on the road in 1970s’ Britain, so they had to make do with vegetarian Indian fare. Then there was the winter weather. “One morning, I woke up and it was snowy,” says Morris. “Bob opened the curtain, and said ‘Wha’ dat?’

“‘It’s snow, Bob.’

“He said, ‘What you mean, snow?’ Peter and Bunny were determined. They said it was a sign from Jah that they should leave Babylon. There was a massive argument amongst them. Peter and Bunny weren’t into the scenario, and Bob was saying ‘We have to continue delivering the message.’ They refused, so the tour collapsed and they went back to Jamaica.”

The story of how Morris found himself on that Transit van is equally extraordinary. The great adventure began in the church choir. “I was a choirboy in the East End,” says Morris. “A very bizarre choir. The church was Church of England. The congregation was predominantly black. The vicar was white, but he had this vision of this choir with choirboys wearing suits, as if they were at Eton. He couldn’t afford it, so he put an ad in The Times looking for a benefactor, and there was this man called Donald Paterson, who was an inventor, a manufacturer of photographic equipment. He made a huge fortune but wanted to put something back. He saw that ad, got in touch with the vicar, and they found out they were both in the war together and became firm friends.

“So Mr Paterson bought the suits. We had to go to Savile Row to get measured as we grew and changed. One of the things Mr Paterson did was he created a photographic club with choir boys. I was nine when I first walked into the dark room and saw one of the older boys by the enlarger with a piece of paper. The image came into the paper - I just thought wow, magic! I knew I wanted to be a part of that. That was it for me. Mr Paterson saw my enthusiasm and my potential and took me under his wings and taught me everything.”

Donald Paterson was a dentist and lawyer with a passion for photography. He invented the self-loading film spiral after taking a picture of a snake swallowing a rabbit while on safari in Kenya. He noted how the snake’s fangs faced backwards, preventing its prey from escaping, and applied the same principle to photographic film. He died in 1975, while attempting to rescue two boys from drowning in Loch Vaa, near Aviemore.

Morris heard of Mr Paterson’s death shortly after he scored his first front cover photograph, with a picture of Marley’s return to Britain a couple of years later. Marley led the Wailers in a triumphant show at the Lyceum in London’s West End. In place of Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, he brought backing singers Rita Marley and Marcia Griffiths. “Bob came back with a vengeance; that thing about the two becoming four becoming six becoming eight. The place was sold out. It was rammed. It was chaos, people were climbing on top of the Lyceum trying to get in. It was so hot inside that all the body heat went up and hit the ceiling and when it came down it was like it was raining. All the Rastas went ‘JAAAAAH!’ It was madness.”

It was Morris’s first time in the photographers’ pit. “But I had something over all the rock photographers. I had seen him before, so I knew which way to be. Every performer performs a different way to the microphone, so I was positioned in the right place. I got the front cover of NME, Melody Maker and Time Out, and that threw me into the music industry.

“It was never my plan to be a rock photographer. I wanted to be a war photographer. I was fascinated by Don McCullin, (Robert) Capa, Tim Page. He was a big hero of mine, Tim Page. He was the photographer for The Doors. When Jim Morrison died he said he had to find another war. So he went to Vietnam. But he was hated by the war photographers because he wasn’t a war photographer. So he took a lot of risks. In the end he got shrapnel in his head.”

One of the things that Mr Paterson imparted was the importance of copyright, which is why Morris has full control of his archive. He also encouraged his interest in reportage. “Documentary, reportage. That’s what I brought to rock photography. Working with the Sex Pistols or Bob Marley, that’s what I did. I did studies, really intimate studies, which is really about catching the other side of the mask.”

Morris’s progress as a photographer is traced in the monograph Music + Life, which stretches from the portraits he took of his neighbours in Hackney to a career in which he became one of the foremost chroniclers of reggae and punk. Those early pictures were his way of earning money for his family, and were taken at home with a bedsheet for a backdrop and a borrowed tungsten lamp.

Morris fell into the orbit of the Sex Pistols when he met John Lydon (aka Rotten) around Hackney. “John grew up in Finsbury Park. I grew up in Hackney. John used to go to Hackney Technical College. So did Sid (Vicious). That circle included (Public Image bass player Jah) Wobble as well. We all used to go to various places.” In what Morris describes as a “cosmic” coincidence, he was trying to get work from Virgin Records when the Pistols signed to the label. “The head of the press office liked my work. She said, ‘Oh, you know what, why don’t you just do some shots of the Pistols?’ And for Malcolm (McLaren, Sex Pistols manager), the idea of this young black guy working with a punk band was perfect because it was so against the grain. That’s what Malcolm was always looking for.

“John and I became friends, and it started from there. He was really into reggae. Everyone in that circle was.”

Morris has said that he has enough photographs of the Sex Pistols to fill a hundred books. His pictures helped define their image.

“For me, the tragedy of it was that John was always forever slagging off Malcolm and (fashion designer) Vivienne (Westwood). The reality of it is, if it hadn’t been for Malcolm or Vivienne, there wouldn’t have been no image. And that’s not taking anything away from John. John is a dynamic, incredible performer, but the image of the Pistols did not come from him. It’s not like you'd say with what’s-his-name from The Jam … Paul Weller. He had that whole concept. But with the Pistols it was Malcolm and Vivienne who really created all those images, with the work of Jamie Reid etc. When I was brought in, Malcolm and Vivienne realised, ‘Oh, he gets it.’

“The unit was kind of strange, because John, visual image-wise, really worked at it. Whereas Sid (Vicious) just got up, put on the jacket. Sid was an absolute natural. So that whole thing just came together, quite organically. I never had to say to John, ‘Do this’ or whatever. For me, it was all about reading him as an individual, reading Sid as an individual, just waiting for those moments, because with Sid, everything he ever did was going to lead to something. You just had to be aware of that and get it.”

Morris recalls a photograph he took after a Pistols gig in Coventry, when his hotel room was adjacent to Sid’s, and his sleep was interrupted by “an almighty racket” from next door. Eventually, the noise stopped, so he got up and pushed the door open to reveal a scene of carnage. “It was like a warzone where there had been a direct hit. Anything that could be smashed was smashed, he had set his bed alight, and I just got these amazing pictures. And there he was lying in the middle of it, passed out. So the idea of rock ’n’ roll being a TV going through the window; oh my God, this was more than that.”

Morris’s professional relationship with Lydon deepened when the singer left the Sex Pistols. It was another cosmic moment. Lydon didn’t know what to do, and Virgin Records wanted to keep hold of him. Virgin boss Richard Branson was busy with a plan to sign up Jamaican reggae acts, and was taking Morris along. “I’d been to Jamaica a few times with Bob, so I had those connections. So I said ‘Why don’t we take John as well? He’s lost, he doesn’t know what to do.’

“So the three of us got on a plane a couple of weeks later and it was really bizarre because when we arrived in Kingston, came out of the airport, there was this group of Rastas. They saw John and they went ‘Johnny Rotten maaaan!’ and I knew from that moment we were going to be cool. Then, just using my connections, we went around. I knew U Roy really well, I knew Big Youth, Lee Perry. So John was going from studio to studio hearing music at source, so that was an influence realistically on the sound of Public Image.

“By the time he came back, he said ‘I want to create a band,’ so he brought in Wobble playing bass, (Keith) Levene on guitar, and then the whole team just came together.”

When Public Image Ltd was formed, there was a lot of conceptual talk framing it as a kind of creative collective. By this time, Morris had met Terry Jones, the former art editor of Vogue who started i-D magazine. Jones encouraged Morris to think about design, and was also fond of abbreviations. So when Lydon explained the concept of Public Image Ltd, Morris said: “Why don’t you call it PiL?” A logo based on an aspirin was produced. “For me it was perfect. It gave me an opportunity to put things together, almost like they were guinea pigs, because everything was just so experimental.” Morris designed the covers for PiL’s first two albums. “The idea for the cover for the First Issue ... I was working with Rose Royce, who had a massive hit with Car Wash. Working with them was my first exposure to the big American music scenario where on the road they had wardrobe, they had makeup, the whole shebang.

“John was adamant about how he wanted to kill the Pistols’ image. I said ‘I want you to go into make-up’. It didn’t take any persuasion for John, so we got the clothes together, a load of zoot suits, then we did the make-up. At the end of the day, they loved it.”

The sleeve was based on various magazines. Lydon was styled after Italian Vogue: L'Uomo. On the reverse, was Wobble, with the Time Magazine typeface. The inner bag was Keith Levene as Mad magazine, and the drummer Jim Walker was Him, the gay magazine, “so it was all playing characters.”

Morris suggests that PiL’s makeover influenced the style of the burgeoning New Romantic movement. PiL’s playful take on corporate culture was also widely mimicked by bands such as Heaven 17, who worked under the aegis of the British Electric Foundation (BEF).

PiL’s second album was more conceptual still.

“A lot of these things came about because there was a lot of substance abuse in those days,” Morris says. “John said the next album is called Metal Box. I said, ‘Oh, Metal Box. You know what? Across the road from my secondary school is the biggest factory called the Metal Box factory.’ I used to pass it every morning. I said, I must go and check out what they do. So I went down there, and it turned out they made film canisters. And I’m like, ‘Wow, the same size as vinyl.’”

The design of Metal Box, though hugely impractical, is one of the great record sleeves, but it marked the end of Morris’s association with PiL. “Things were starting to fall apart with PiL, because there was a lot of egos, in particular with Keith Levine. He was a really heavy junkie. He hated the fact that Wobble was on the B-side of the bag (on First Issue) and he was on the inner sleeve, cos he thought ‘I’m a guitar hero, I should at least be on the outside.’ He hated me for that. So when I put together the idea for the Metal Box, there’s lots of arguments. And I just said, ‘You know what? Fuck it.’”

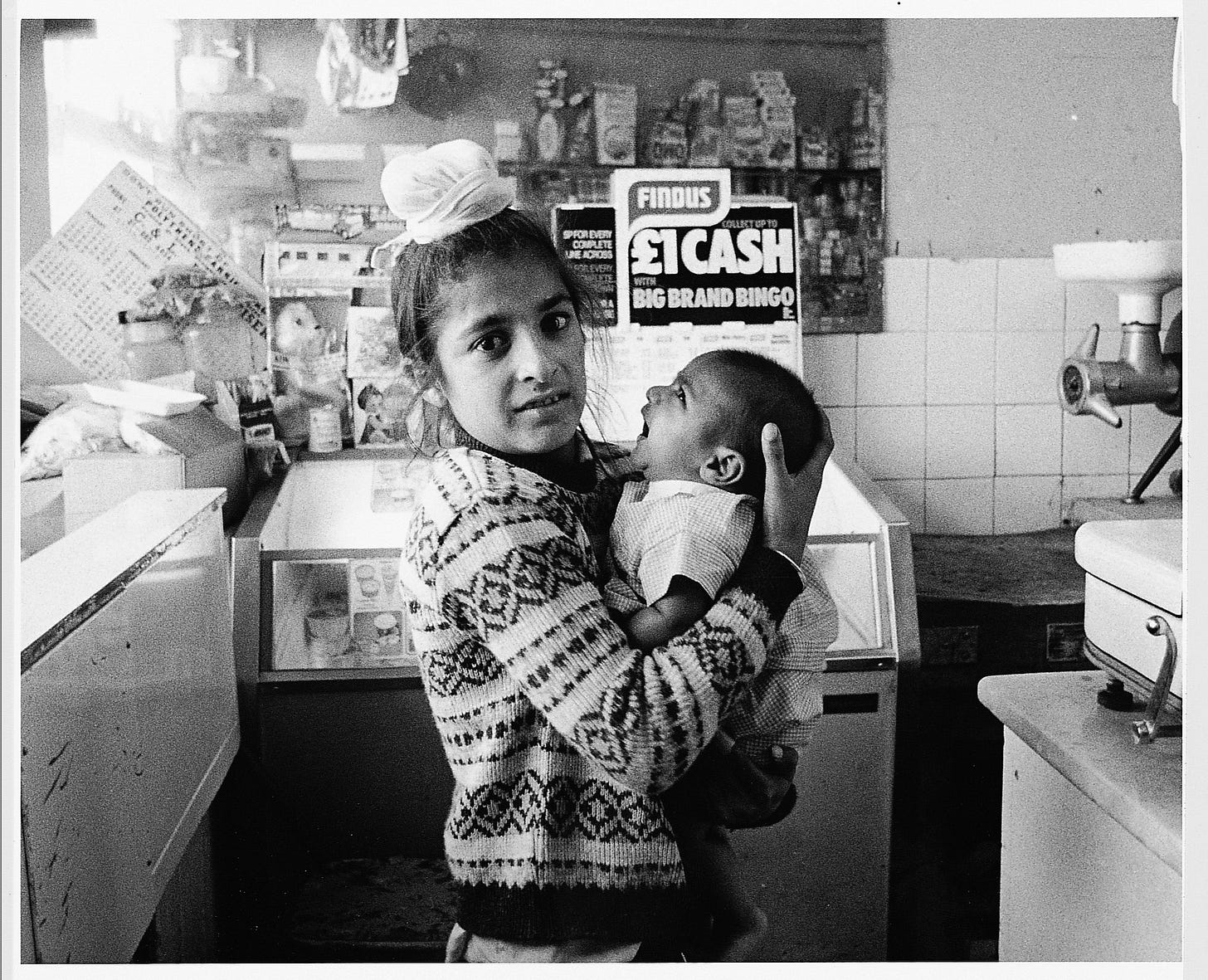

Morris’s work with PiL led to a phone call from Island’s Chris Blackwell, who confessed he had made a mistake by not getting involved with punk. He offered Morris a job as the label’s art director. Morris replied that Island had no interesting acts, but suggested that he might be interested if he was able to work with emerging talent, such as dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson and the all-female punk group, The Slits. Blackwell told Morris: “You sign them, and you oversee it all.”

Johnson’s second album, Forces of Victory, was a triumph, with the poet’s sombre verse framed against the cool reggae rhythms of Dennis Bovell. Morris’s design concepts included fashioning an LKJ logo onto an old BBC microphone, and - for the following LP, Bass Culture, a silhouette of the poet going down a staircase, as if to a basement blues dance. To get the image, Morris flew to Berlin, hired a taxi, and photographed a subway sign before flying home to make a print.

The Slits’ album - though now acknowledged as a classic - proved more problematic, and Morris is unhappy about being called a “cunt” in Viv Albertine’s memoir Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys. “The Slits was a bit of a nightmare,” Morris says. “Basically, Chris didn’t want to sign them. But he said to me, as long as you oversee it, I’ll stay with it. So when I signed The Slits, I don’t know what happened, but it went to their heads. And in particular, the guitarist.

“They had a great opportunity, and they blew it. What was really weird about it: 20 odd years later, I’m in Jamaica, and I’m sitting there by the pool, as one does, drinking a cocktail. And this girl comes up and it’s Ari” - Ari Up, the Slits’ singer - “and she says, in this German accent, ‘Ah, it’s Dennis, you were so right, we were so stupid zen.’ I looked at her and I said, ‘Ari, forget it, it’s over.’”

When he reflects on his career, Morris cites a favourite book, Meetings With Remarkable Men by GI Gurdjieff. His own list of remarkable men includes Mr Paterson, Bob Marley, Chris Blackwell, Richard Branson and Terry Jones. There may also have been an element of chance. It was Morris’s cosmic good fortune to find himself at the convergence of reggae and punk.

“Punk rebelled against the established rock sound,” he says. “And the only music that was around that was saying anything as rebellious as punk was reggae. It was a perfect union.” His approach has been consistent throughout. “It’s all about moments,” Morris says, citing the influence of Irving Penn. “All those images, everything I’ve ever done is about those moments.

“What I learned from Bob Marley was spirituality, a sense of being, a sense of holding things together. What I learned from punk was how to kick the door down and take what you want.”

Dennis Morris: Music + Life is published by Thames and Hudson, £40. An exhibition of the photographs runs at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, from 27 June 2025 - 21 September, 2025.

He was one of the great photo chroniclers of two massive musical movements: punk and reggae’s move into the mainstream through the UK scene.

And, of course, he was a great snapper!

Terrific read, Alastair!

Good story. 'John Lydon with cigarette' is a mag editor's dream.