Skinheads, Slade, and the Everlasting Beauty of Yob Rock

The re-release of the film Slade In Flame after 50 years prompts a re-appraisal of a very British success story

You only regret the photos you don’t take. The photo I took frames a portion of the wall of the North Berwick Playhouse. It shows the window where the stills from the coming attractions were posted. Jaws, The Man With The Golden Gun, The Omega Man. At the moment of the picture, NB had no coming attractions. The cinema was condemned, soon to be demolished. On the wall a wag had chalked FREEDOM FOR NORTH BERWICK/BRITAIN, FREEDOM FOR ME. I didn’t do the chalk, but that was teenage me.

The picture I didn’t take would have shown the whole of the cinema building, including the first home of the record shop, The Melody Centre. In the darkroom of memory I see the sleeve to David Bowie’s album Pin-Ups, a study in airbrushed alienation. The punk singles are lined around the window bay. God Save The Queen by the Sex Pistols has its sleeve reversed, so as not to cause offence. Next to it is a record by a peroxide new wave band called The Depressions. I bought that 45 on the basis that The Depressions were managed by Chas Chandler. After about 100 plays, I conceded I had made a mistake.

Why Chas Chandler? Not because he was in The Animals or because he managed Jimi Hendrix. I knew these things but didn’t care. I trusted Chas because he managed Slade, and Slade were my teenage crush. Slade Rooled, OK, and that wasn’t even a question. I had a scrap book, a Super Slade patch on my denim jacket. I had the records. And that is why I stared at the coming attractions. I was waiting for the Slade film, Slade in Flame, but Slade in Flame never came.

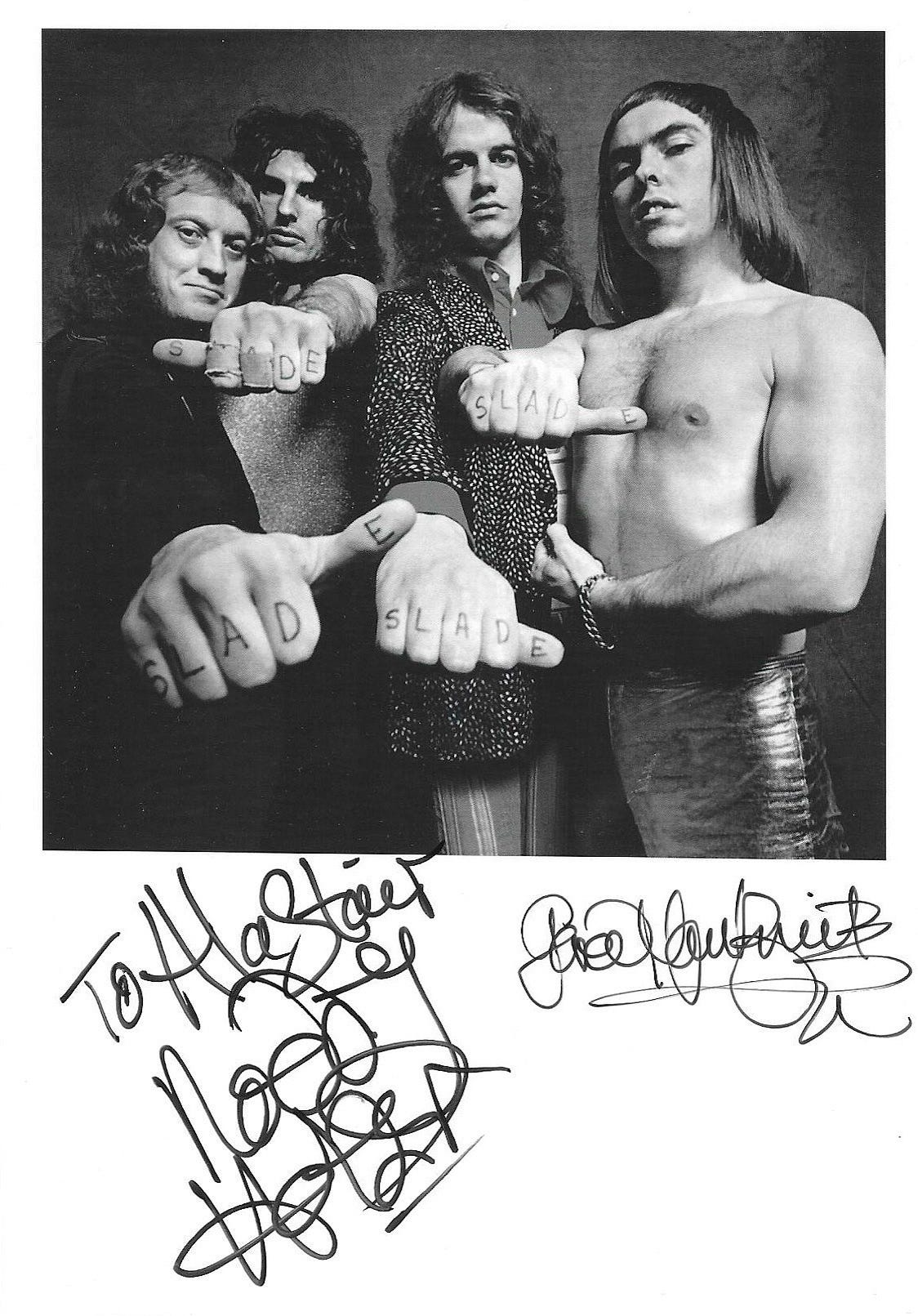

In my Slade scrapbook, the pictures come from magazines that no one remembers. Fan, Disc, Pop-Up!, Pop 73, Popswop, Mates, Music Star, Disco 45, Fab 208 - publications with a democratic approach. They were designed for girls. I didn’t notice. The scrapbook is ripped and torn. The Sellotape has yellowed. The Pritt has dried. Everything is there, jumbled.

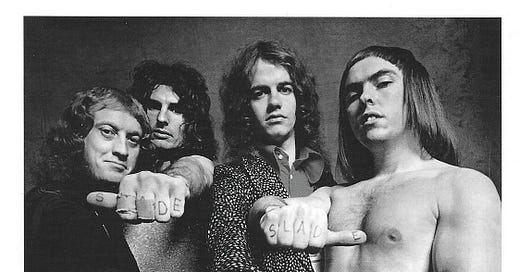

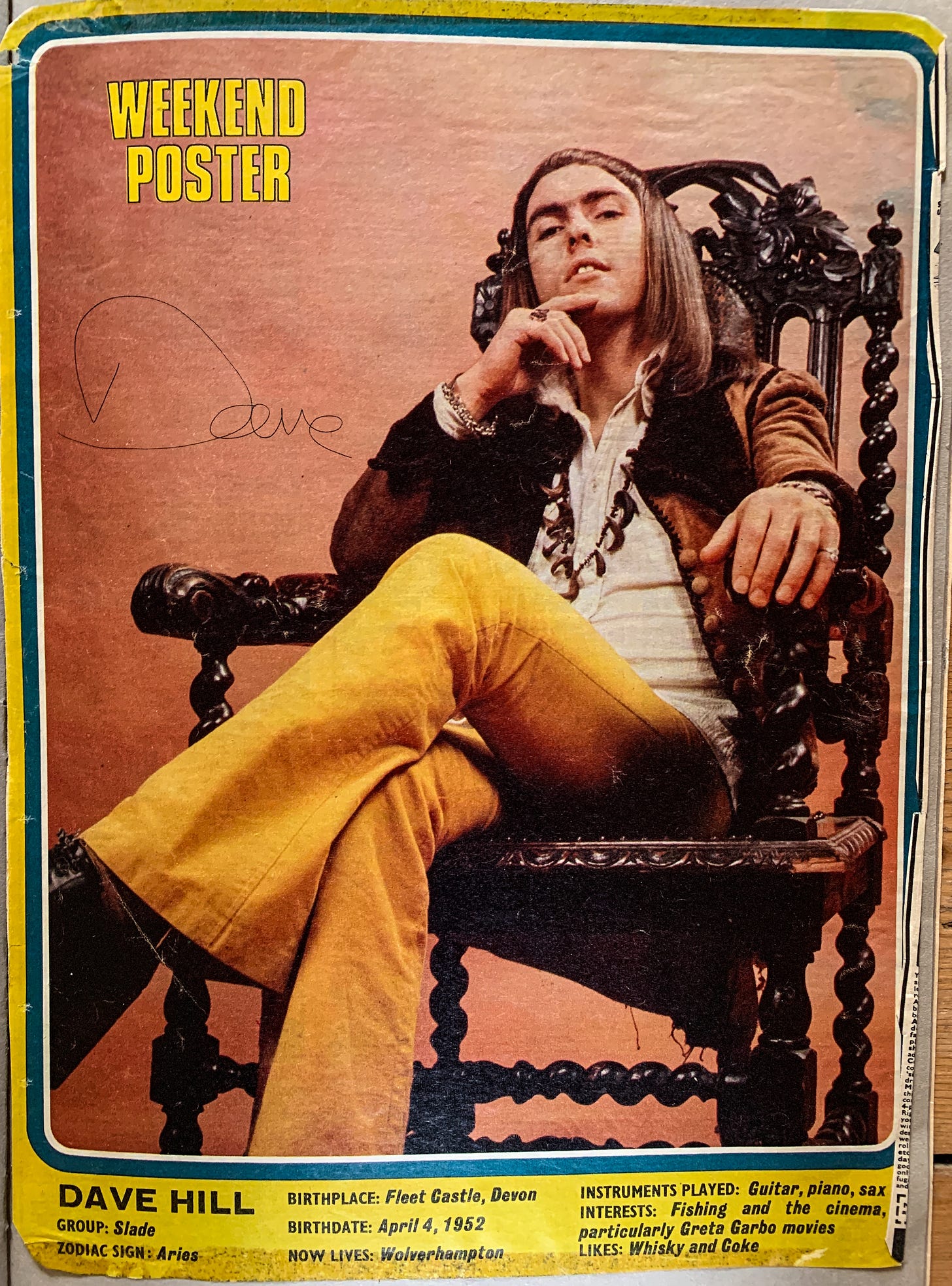

What was it about Slade? They were louder, bigger. They were very male, which hadn’t been diagnosed as a character flaw in 1973. Dave Hill, the bacofoil-wrapped guitarist, had a Rolls-Royce with the number-plate YOB 1, and a Super Yob guitar. Other groups of the glam era had one effeminate member, with more extravagant make-up, broader flares, a pout. Dave represented the far borders of Slade’s glam styling. He went far, but no further. In a Melody Maker interview, Dave mentioned that his Super Yob image was invented with the help of an art school student called Steve Megson, whose father ran a jazz pub in Bilston, Wolverhampton. The clothes were Dave’s ideas, made real by Steve. They were mad: harlequin dungarees and space age shoulder pads.

“My idea of a really flashy yob is to make it look butch,” Dave explained. “Not poufy. You see big blokes looking like poufs now, they may have glitter or make-up on, but the thing is they look at it in a different way now. When I first did it, it was ‘He must be a queer’, but people have now accepted the fact that it’s not true so, therefore, the situation has matured. Personally, I’m not into make-up. Basically, what I use is sparkles and the clothes and the big boots for stamping - it’s all got a positive connection with what we’re doing.”

It was a different time.

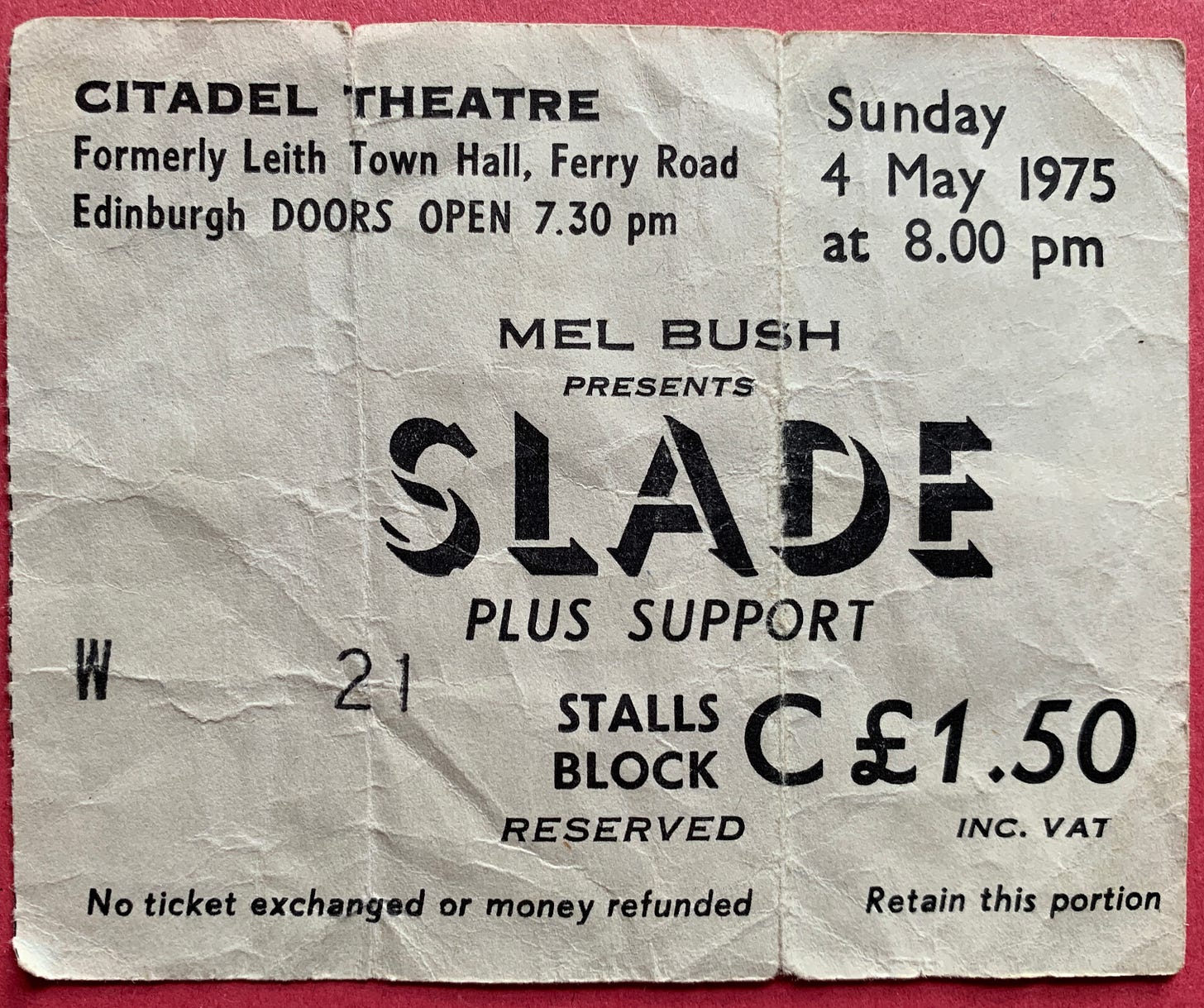

So. I had a wallet. It was textured plastic, man-made crocodile, and had a picture of a Chinese pagoda on it. It was a gift from Hong Kong. Our old neighbours, the Woolleys, had been out to the colonial island and brought the wallets back as gifts, along with red and gold Mao badges. I rarely had paper money, so the wallet was only theoretically practical. Until I got a ticket for Slade.

In 1975, Slade announced a date at the Citadel Theatre in Leith. I was just about old enough to go. My pal Kendo and I journeyed to Edinburgh, and queued impatiently outside the box office. The tickets cost £1.50 and were printed on yellow paper, with the band’s name rendered in Umbra, a shadowy, thin font. This ticket was my passport to dreamland. I carried it in the fold of the Hong Kong plastic crocodile pagoda wallet like a charm.

I set about gathering a mid-1970s wardrobe. There were rules; unwritten, understood. Personally, I wasn’t into make-up. Jeans should be Wrangler. By virtue of easy availability at East Fortune Sunday market, Brutus high-waisters were permissible, though they carried a whiff of soul-boy. All other jeans were derided as “Bobby Washables”.

A Slade stage outfit was not an easy thing to achieve. The barber had a freezer full of meat in the corner and a ladies’ salon next door where on a Tuesday night, girls would wash your hair and cut it into a feathery nest: an excruciatingly sensual experience. Thankfully, Slade didn’t maintain the full Dickensian space urchin look off stage. The achievable things were the neon stripy socks, but to make them work, you needed the shoes.

Oh God, the shoes. A scrapbook article from Disc (Putting The Boot In Pop! by Lynne Thirkettle) offered a thoughtful survey of glam footwear. Elton John had a hundred pairs of “ankle-breakers” in his wardrobe, Lynne revealed. Some of these were ready-made, similar footwear could be found at the King’s Road shop of Terry de Haviland, a shop also favoured by Steve Priest, the glamorous member of The Sweet. (Terry’s rock and roll shoes were also available at Baffies of Morayshire). Roy Wood of Wizzard favoured boat-style clogs similar to those sold by Olaf of Sweden. Rod Stewart, disliked “silly” shoes, favouring Fred Astaire patent numbers and finely-made lace-ups “with a subtle brogue look”.

And Slade? Mixed messages. The offstage photograph showed Noddy wearing three-tiered high white lace-ups on a wood heel. (“Noddy has been known to wear plimsolls off stage.”) Dave had knee-length white leather boots with red leather dollars and red triangles on the platform and a high heel. (“They make me feel taller, said Dave, 5’3”). Jim Lea wore beige leather lace-ups on a wood heel with a blue snake strip running through the platform with an “almost Paisley” print. Drummer Don Powell’s feet were encased in knee length black leather boots on a three-tiered platform and wood heel. “Two inches is about my limit,” said Don, “otherwise I find I can’t play the drums”.

North Berwick High Street had its charms. You could buy a stick of rock, a garden gnome or a vibrator. But not fancy footwear. There was a shop full of Polyveldts, or there was the Co-op, where the foot measuring was done with a fluoroscope X-Ray machine. For stupid fashions, you had to go to Haddington.

It was not a stressless afternoon, trying to buy glam rock shoes in Haddington with my mum. Eventually, we settled on a pair of plastic brothel creepers with an elevated heel. There was a question about whether they were girls’ shoes, but I summoned my inner Dave Hill and tried not to worry. They were good enough, which was better than embarrassing. (My dad would have disagreed. When I paired the plastic brothel creepers with a pair of brown high-waister bags in a man-made fabric, he took one look and said: “You will never be allowed to choose your trousers again”).

We were in the car, leaving Haddington, when I noticed that the Hong Kong pagoda wallet was not in the pocket of my Bobby Washable jacket. I searched again. First in the pocket with the Super Slade patch, then in the pocket with the Union Jack Victory-V sign. Nothing. The wallet was gone, and with it, my dreams.

I dragged my mum back round the infernal gutters of Haddington, retracing our steps. Shoe shop. Wool shop. Cafe. Nothing. Defeated, we adjourned to the police station to report the loss, where a miracle happened. Someone had handed the Chinese pagoda crocodile wallet in, and the ticket was still inside.

The concert was the best. It remains the best. It will always be the best. It was a riot of noise and chaos, a swell of joy and incredulity, and great warm blushes of that very adolescent sensation where innocence is lost and found in the same instant. I couldn’t believe it. Slade existed and were in the same room. They were up there on the stage of the Citadel, and the entire audience was standing on the seats, untamed. The night flew past.

My friend Kendo and I floated out of the Citadel, pausing to liberate album covers from the merchandise stands in the foyer. It was joyous mayhem on the streets of Leith, then the crowd disappeared. Standing on the kerb, waiting for our lift, we were surrounded by skinheads. There was a flurry of grabbing and punching, then the skinheads of Leith made off with our merchandise. By the time Kendo’s father arrived in the car, we had made a pact to say nothing about the violence, because we would never be allowed out of our houses again.

It was all right. It was better than all right. My face was bruised, my ears were numb. I had a Slade badge in my pocket, the last souvenir of the best night of my life.

What was it about Slade? At the time, I never asked. Critical thinking is learned, and it doesn’t make things more fun. Slade just were, in the way that the best pop music is. I kept buying their records for longer than was strictly necessary. Over time, I stopped playing them, and they slipped from view. I never saw Slade again, and Flame never came to North Berwick.

And now, here I am, 50 years later, in the Iconic Images gallery in Piccadilly, listening to Noddy Holder and photographer Gered Mankowitz swapping Slade stories. It feels magic. Just seeing Noddy is a thrill. After a spell of illness, he looks and sounds in rude health. He is dressed in a Rupert Bear suit, and his voice is so loud that when he talks into a microphone it sounds like thunder. “I’ll project,” he says after a while, putting the microphone down.

It is a nostalgic affair, listening to Noddy and Gered, and much of it is about image. In certain photo sessions, Noddy says, “Dave would want to go over the hill. He’d want to go on another plane. Now, Jimmy was not having this. Jimmy quite often threatened to walk out of sessions when Dave went over the top with outfits. Gered had to keep the atmosphere light. It used to happen at Top of the Pops as well. Dave would have a new outfit for each Top of the Pops, and he would never change into the new outfit in front of us. He’d change into the new outfit in the toilet. And the only way we knew he was ready, we’d hear the hairspray and see it above the door.

“His nickname was H. So I’d say, ‘H, come on, reveal! Out he’d come, and Jim would go ‘I’m not fucking going on with that!’ And that is when Dave would say, ‘You write ’em, I’ll sell ’em.’”

The outfits had nicknames too. “He had one where he looked like a nun. Steve Marriott nicknamed it The Metal Nun.” Dave was the same when he wasn’t famous. “He used to walk around in a wizard’s hat. He loves being noticed. It’s like applause is his oxygen. He has to have it.”

Over time, Dave’s eccentricities were accommodated within the group’s image. First, there was the accidental skinhead period, where Chas Chandler took a suggestion from publicist Keith Altham a little too seriously.

“Chas could always talk us round,” Noddy says. “All he had to say was ‘Dave, if you do this, you’ll be a millionaire.’”

“I was taken aback,” says Gered. “Dave looked like a little kid.”

“Dave hated it,” says Noddy.

“And Jimmy,” says Gered.

“Jimmy also hated it.”

“But Don looked really hard.”

The skinhead image backfired. Radio wouldn’t play Slade’s records. TV producers wouldn’t book them. Their only TV appearance was on Alan Price’s show, because he had been in the Animals with Chas.

“I remember one night,” says Noddy, “we were in Guildford and it was a big skinhead area. We didn’t really have road crews in those days, we had to load the gear in. But once we became skinheads, we always carried a loaded rifle in the van. I remember, after this gig in Guildford Town Hall or somewhere, we were sitting waiting to go off and this gang of about 50 skinheads came around the corner who wanted to beat the shit out of us. All I did was wind the window down and I got the rifle and stuck it out. You’ve never seen anybody move so fast. They were bricking it. But we did have to change image to get acceptance in the media.”

On Play It Loud, Noddy wore a flat cap he had picked up at the wrap party for the Jerry Lewis film One More Time, which starred Sammy Davis Jr and Peter Lawford. Sammy Davis sang a couple of numbers with Slade that night.

“The hair grew out,” says Noddy. “We grew the skinhead girl cut which was feathered down at first. We still had the big boots, but it became platform boots. I still wore the braces. Just became colourful. Still wore short trousers, which was the old jeans and Sta Prest trousers, but more colourful tartan trousers. Really it was still a skinhead image. It was just more colourful. So it became more accepted. But Chas stuck with us. Everybody was saying for two years, ‘These are never going to crack it’. But Chas had massive confidence in us.

“Eventually we decided to record the track that was the last number of our show.”

That was Get Down and Get With it, which became Slade’s first hit in 1971. “But Chas said: ‘Your next record has to be your own song.’ He picked on me and Jimmy. Chas was very bombastic, and he said, ‘You two go away and write a hit song.’ I was up in the Midlands, and Jimmy come round with his violin to me mum and dad’s house. And he said, ‘How about that thing we play in the dressing room to tune up the violin?’ It was like a Django Reinhardt, Stéphane Grappelli sort of rhythm thing. So we started chugging, chugging this rhythm, and I sang this melody over the top, and it’s what became Coz I Luv You. We wrote it in 20 minutes. We didn’t even play it to Don and Dave. We took it to Chas and played it to him. Me on acoustic, singing it, and Jim on his fiddle. And Chas said, ‘I don’t only think you’ve written your first hit. I think you’ve written your first number one.’ We were like, ‘Fuck off, Chas! Can’t be that easy.’ So we went in Olympic Studios to record it down in Barnes, but it sounded wet. And we thought, ‘Well, why don’t we do what we did on Get Down and Get With It? Put handclaps, boot stamping, all that on it?’ So we did, and it came alive. We Slade-ified it.”

The sound of Slade can be attributed to Dave. “Dave’s idea was to have three guitar players,” says Noddy. “Because Jim’s not a conventional bass player. Jim plays bass like a lead guitar. So I was lead guitarist and singer when I joined, Dave was obviously a lead guitarist. So we used to have three, what you’d call lead guitars on the band. It was all in harmony, but with three leads. And it worked on that first afternoon. We thought, we’ve got some magic here.” To this, you might add Jim Lea’s classical training, and Noddy’s love of 1950s’ rock ’n’ roll, particularly Little Richard. Slade’s hits have a policy of total exuberance that owes a lot to Little Richard. Or, as my copy of the 1973 fan magazine Slade Alive! has it: “Noddy’s snarling between numbers is part of Slade. Dave’s glitter, garments and gavotting is part of Slade. Jim’s bass patterns and his charging across stage is part of Slade. And Don, with his gum and Long John Scotch, battering out the back-beat is part of Slade.”

And so to Flame, the part of Chas Chandler’s masterplan that didn’t work, and set in train Slade’s commercial descent. “It was his idea to do a movie,” says Noddy. “He always followed the Beatles blueprint: get a number one, get another number one, go straight to number one.

“We were just the tool, for want of a better word, to put that plan into action. Chas really wanted to be a film producer, and he said, ‘We’ll make a movie next.”

The first script, a Quatermass spoof called The Quatermess Experiment, was rejected by Dave because his character was eaten in the first 20 minutes, and he spent the rest of the film being a hairpiece in the monster’s mouth

Richard Loncraine was hired as director, and Andrew Birkin (Jane’s brother) was commissioned to write the story. “He was a weird character. Before the term gothic was invented, he was a pre-goth.” The first draft told the story of an up and coming group in a way that didn’t ring true, so Slade invited Birkin and Loncraine on the road in America. “They lasted two weeks. They came back with nervous breakdowns, but they did have a script.’

“Of course, what we didn’t know was they were looking at our personalities, because we weren’t actors. They were looking at what we could get away with on screen. More or less they wrote the characters based on our personalities, and we got away with it.

“The movie worked out. The critics were good to it, but the fans didn’t want it.”

And so it is that, half a century later, I am in a screening room in Soho, watching Slade in Flame. It is an extraordinary film, forensic in its lack of glamour. There is a wedding band, a ruffle-shirted crooner, a motorcycle sidecar, a budgerigar, a neck brace, a scene in which the bingo is disrupted at a working men’s club. Noddy, borrowing from Screaming Lord Sutch, performs inside a coffin, but gets locked inside and misses his cue. There are cravats, cheap glitter, terraced houses getting boarded up, Noddy tending to his pigeons, Dave playing with a pair of pants hanging from the end of his guitar. There are two scheming managers, one a criminal, the other posh. It is abrupt, bleak, edgy. The obvious irony is that Slade spent a large part of the mid-1970s trying to break America, and they made a film that couldn’t have been more British. It is not glam. It is about class. It is about packaging. It is about the dishonesty and artifice of the music business, which Don Powell sums up as “a bunch of bleeding gangsters in dinner jackets.”

“I’m not the vocalist,” says Noddy, “I’m the singer.”

“I’m not a bloody fish finger,” says Jim Lea.

In the marketing of the film, much is being made of Mark Kermode’s assertion that Flame is “the Citizen Kane of rock movies”. It isn’t, of course (the smart kids say that is Stardust). I’d turn the mirrors on Noddy’s top hat in the other direction and say that The Great Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle is Flame with an art school education, and punk owed more to Slade than anyone ever admitted.

I queue up to say hello to Noddy Holder. It’s not often you get to meet people who exist in your imagination. I mention Leith Citadel. I tell him it was great, and then I was attacked by skinheads.

“You should have taken a shotgun,” Noddy Holder says, signing my copy of Slayed? across the tattooed knuckles of his right hand.

(An earlier version of this appeared in my book Alternatives To Valium: How Punk Rock Saved A Shy Boy’s Life. It is available from Waterstones’ website.)

Thank You for this...loved it! Made my week so much better.The coolest parts for me were when you described the shoes...that really takes me back. I was heavily into T-Rex and Marc Bolan at the time; always trying to dress like him...it made me so happy even though I looked ridiculous! I couldn't pull off his coolness,but I loved dressing like him...

If there was a British rock'n'roll record coming out of the early seventies with more sheer primeval power to it than SLAYED? I've yet to hear it.