Resins To Be Cheerful: The Beautiful Secrets Of My Mother's Shellac Record Collection

Behind The Golf Clubs and The Dusty Bibles In The Wasp-Infested Loft, I Found A Pile of 78rpm discs. It Was Like A Message From Another Time

A few years ago, I found myself at the head of a queue in an old London church waiting for Nick Cave to sign a book. The book was Carnage. It’s a very good book. There was something about Nick Cave’s demeanour that night that was inclusive, so getting an autograph felt less weird than it sometimes does. Actually, I went further. I got a selfie too. And in the awkward moment between signature and pose, I felt I should say something.

I asked Nick Cave whether he had read Michel Faber’s The Book Of Strange New Things. Why did I say this? Because - hint of a spoiler - Cave’s album Ghosteen reminded me of The Book Of Strange New Things which … well, you should read it. It will work better if you don’t know what’s going on. And you won’t know what’s going on. It’s liminal.

“Is that the one about space?” Nick Cave said, indicating he had seen the book, but hadn’t got on with it. I said, yes, it was the one about space, but it was really about grief, or perhaps the anticipation of it. (Michel Faber’s wife Eva died in 2014 after a long illness). It occurred to me, slightly too late, that Nick Cave probably didn’t need any help with a reading list on the subject of loss.

The Book of Strange New Things was Michel Faber’s last book of fiction for adults. It was published in 2014. Faber said at the time that he felt he had “written the things I was put on earth to write”; an oddly fateful thing to say. But it wasn’t the end of his writing. There were some poems, then in 2023, he published Listen: On Music, Sound and Us, a book I’ve had by my bedside for two years. Well, you know, delayed gratification.

Now I’ve read it. What a strange book. It pitches between an argument and a phD. It is Michel Faber writing, so the discourse unfolds with an odd sense of time. Possibly it’s pandemic time, that state of limbo where nagging thoughts had nothing to interrupt them. On several occasions the author refers to the editing process, and the fact that his original text was much longer, more detailed. He seems peeved about the cuts. I can relate. What’s also strange is that his discussions about music are illustrated with comments from YouTube, which must be the lowest form of literature, excluding TripAdvisor reviews (“Delicious burger, I will definitely be dreaming about my meal for awhile,” says Megan C of the Hard Rock Cafe). A bit more blue pencil would have helped.

The book is about music. It’s also about alienation, critical judgment, taste, Val Doonican. All the shit. It has an odd aftertaste. As with The Book of Strange New Things, and the alien hitchhiker novel Under The Skin, it feels like an exploration of distance. The author likes music (June Tabor; Two Little Boys by Rolf Harris) but is entirely unsentimental about it. A record he gifted to a loved one is described in a chapter called A Thing That Takes Up Space And Merely Gathers Dust.

One chapter got to me. The charity shop chapter. Charity shops, as charity shoppers know, are a place of final reckoning, because the racks are filled with the record collections of the deceased. Decades ago, it was possible to find bargains, but charity shops are professional now. Prices are copied from the valuations on discogs.com. Interesting records are siphoned. Only the disreputable make it into the racks. Faber mentions Doonican, Shirley Bassey, Jim Reeves - records that were bought in vast numbers in the 1960s and 1970s, but have since misplaced their audiences. To these, he adds more recent victims of changing taste: Phil Collins, Dire Straits, ABBA and Neil Diamond. (A surprising list, as all of these acts remain popular, but maybe not among the clientele who fetishise vinyl. Where is Paul Young’s No Parlez?)

“How bad is Val Doonican?” Faber writes. “As ‘bad’ as Bruno Mars or BTS or Jon Batiste.”

How bad is that? (Hold on while I Google BTS). Well, the author suggests, Doonican was a “run-of-the-mill entertainer servicing the ephemeral needs … All too soon, Bruno Mars will twinkle out of mainstream consciousness and sink into the underworld.”

Faber writes about the music he heard in his house while growing up. His father’s record collection was “all charity shop material”. There was Jim Reeves, Greek folk, The Heavenly Sound of Negro Spirituals, schlager - the coolest record was a budget Duke Ellington collection. “My mother didn’t care for music much. She preferred knitting, and the ticking of her cuckoo clocks in the stillness.”

This is the point where the author reached out across time and space to shake hands with this reader. Because I recently discovered something.

In the story I used to tell of my childhood, my parents showed few signs of being interested in music, beyond asking me to turn it down. Some of these childhood memories are fading. There is a loss of focus around the edges. A bit of fogging. Things that used to be true are now in dispute.

Each of us moulds the family story in our own image. We forget, we embroider, we misremember. We make it up. Photographs help, though they tend to record Sunday Best occasions. And with some things, there is no way of checking. Decades ago, my mum told me about seeing Frank Sinatra in the Caird Hall in Dundee. His popularity was slipping, those blue eyes no longer dazzled, the venue was half empty. The internet may reveal that such an event never happened. If so, don’t tell me.

Why have I hung onto that memory? Possibly because it hinted of a life that was hard to imagine. It was a detail on the blank landscape - the lives of my parents before they had children. As a parent with no life, I appreciate the topology of this void. Some things are beyond the curiosity of children, and then they are gone.

My mum and dad were war children and post-war parents. They often talked about “settling down”, as the ultimate aim of life. This is not what teenagers wanted to hear in the 1970s, and nor was the concept easily achievable. We didn’t settle down. We signed on. I got a degree, but the qualification that got me my first job was being unemployed for more than six months. I managed two years of enforced idleness. I was an over-achiever. (Namedrop #2. I once mentioned the concept of settling down to the author Richard Ford. He suggested that the equivalent in his American upbringing would have been “starting out”. That’s the difference between Calvinist Scotland and the new frontier).

But if the Frank Sinatra thing happened, it occurred in an earlier time. By the time my parents were parents, there wasn’t much sign of them having an interest in music. The Beatles didn’t occur in our house. My dad had a thing about Barbara Dickson, but it wasn’t entirely about her voice. My parents didn’t get a stereo until the mid-1970s. For a while, the only music we had was a reel-to-reel tape of The Sound of Music. I have a memory, more to do with travel sickness than music, of sitting in the back of our battleship grey Vauxhall Victor while my dad sang Green Green Grass of Home with comedy lyrics. “Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone…” But no, I can’t remember the joke.

Eventually, after witnessing my Uncle Jimmy’s demonstrations of the miracle of stereo - a process which required a heightened appreciation of Hocus Pocus by Focus - my dad bought a music centre. There were a few records too. Some of these were gifted by me or my brother in an attempt to improve our parents. (Other attempts at child-to-parent gentrification included a lava lamp, and a coffee percolator. The lamp was wildly inappropriate. The percolator came out every Christmas, with the same years-old jar of coffee. It tasted far worse than Mellow Birds.)

So, there was a Joan Baez album, and Bridge Over Troubled Water by Simon and Garfunkel. Records that appeared from nowhere included a few classical compilations from the Your Hundred Best Tunes series, and an Observer box set, Great Symphonies Vol. 2. I used to listen to the Great Symphonies when I revised for exams. I still have the box. I played it today. Whether the symphonies are great or not, I have no idea, but for classical ambience, it can’t be beat.

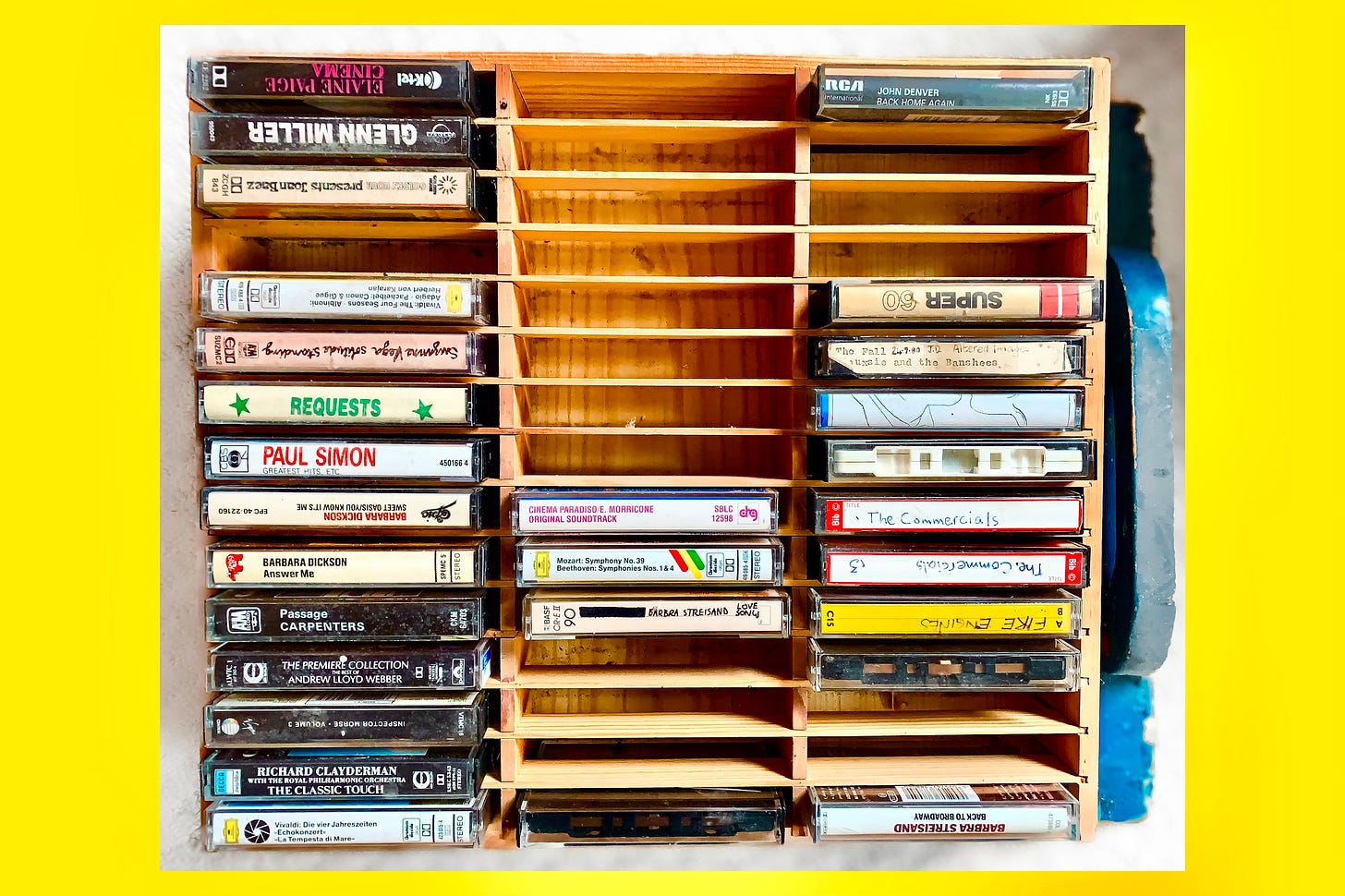

The discovery? While excavating the loft of the old family home in the middle of the pandemic, I found a few cassettes among the things that took up space and gathered dust. Some of the cassettes were mine. There was a tape of Fire Engines, a live recording of my band The Commercials, and a tape of the John Peel show including The Fall, Altered Images and Siouxsie and the Banshees. The box also contained another Baez album, a couple of Dicksons, Passage by The Carpenters, the best of Andrew Lloyd Webber, Paul Simon’s Greatest Hits, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Glenn Miller, and - a classical compilation - Inspector Morse, Volume 3.

This was the version of my parents’ musical taste I knew about. Easy listening. When I think of the hours my mum sat there, uneasy in her easy chair, as I subjected her to the wiry angst of David Bowie’s Lodger, I have nothing but admiration. No wonder she went for In The Mood.

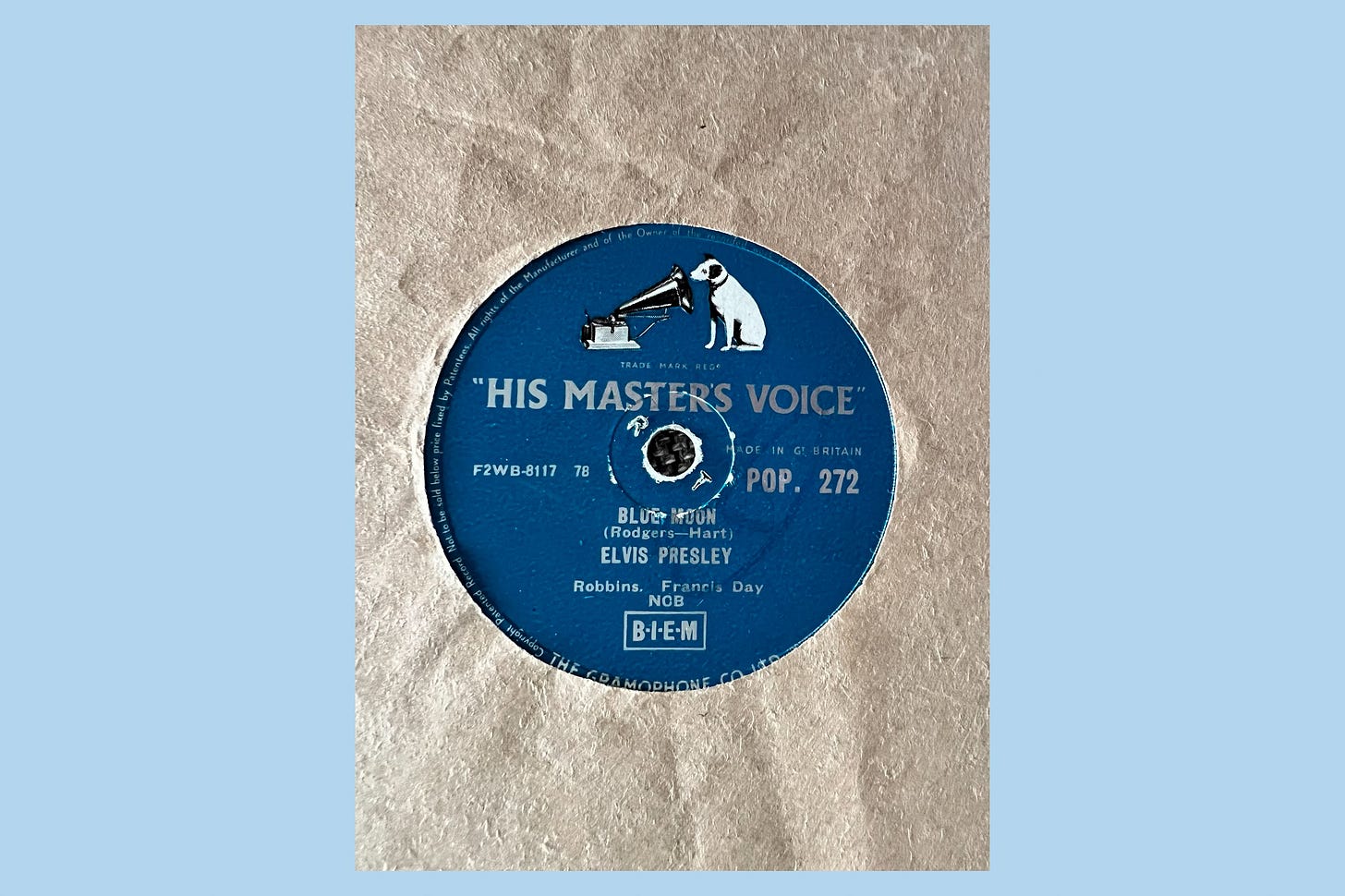

But there was more. In the wasp-infested loft, hidden beyond the golf clubs and the old Bibles, I found a pile of shellac 78s. They are beautiful things. The brand-name poetry of Zonophone and Panachord, Broadcast, Piccadilly, Beltona, Electrographic, Songster, Petmecky - all of it rings with the promise of technological advance. But what of the music?

Well, my record player has advanced to the stage where it disapproves of 45s and can’t deal with 78s, but thanks to streaming and the instant availability of everything everywhere all at once, I am able to recreate the sound that would have echoed around my mum’s house in the early 1950s.

What was on this mix-tape from the underworld? Some of it I knew. Bing Crosby’s White Christmas was old even by the time this edition of the record was released. It appears on the b-side of another seasonal effort, Let’s Start The New Year Right, a glorious croon that manages to be romantic, nostalgic, and optimistic, all in the same phrase. Bing’s singing may now be the set up in the Scottish joke about Walt Disney, but he’s a genius of intimacy. Kissing the old year out, kissing the new year in. It’s a lot of kissing.

Beyond that, these records mostly date from the mid-1950s. Taken together they represent an absolute maelstrom of musical styles. They hark back to the orchestral sounds of the war, sideways to country dance music, and forward, to rock ’n’ roll. There are great slabs of melodrama, novelties, campfire cowboy ballads.

It is, in its way, the soundtrack to a fantasy world. There are songs from the movies, and dance records, many of them performed by artists with foreign-sounding names. Some of the artists have disappeared without trace. You can google Eve Lombard and find nothing beyond a vague suggestion that her real name was Margaret Enda Farrell. But there’s no escaping the sentimental power of the tune Whatever Will Be, from the 1956 Alfred Hitchcock film The Man Who Knew Too Much. Doris Day won an Oscar for her performance of that song, and there’s another of her recordings in the dust pile. Did my mum like Doris Day? She didn’t get out to the cinema much in her parenting years, though I did once find a few movie magazines in the airing cupboard. The only clue I garnered about her cinematic tastes was the eavesdropped suggestion that Gregory Peck was handsome. I innocently repeated this at school in primary six, when we were asked to define a handsome man. The curriculum was strange back then, but the teacher, Miss Thorburn, was charmed.

And look - surely a biography waiting to be written - here is Billie Anthony, real name Philomena McGeachie Levy, a singer from Glasgow whose father was the stage manager at the Glasgow Empire and whose godmother was Gracie Fields. Billie was a one hit wonder with This Ole House, and quit the stage in 1960, saying “I’ll let the rock ’n’ roll boys come and go and then I’ll be back”. The irony for Philomena was that This Ole House became a hit for the communist rockabilly revivalist Shakin’ Stevens in 1981. It is, when you scrape beneath the jittery rhythm, a singularly bleak lyric, written by singing cowboy Stuart Hamblen after he and John Wayne uncovered a dead man inside a tumbledown hut in the Sierra mountains. Nick Cave couldn’t write a song as bleak as This Ole House. “I feel no fear or pain/‘cause I see an angel peekin’ through a broken window-pane.” So bleak was the song that Hamblen was able to spend the royalties from it on Erroll Flynn’s haunted house up on Mulholland Drive.

Back to the dust pile. There is country music. The Hill Billies’ Ole Faithfull is all harmonica and cowboy campfires. It is really quite lovely - “hurry up old fella cos the moon is yella tonight” - and appears to be a song addressed to a cowboy’s horse … there is clip clop percussion, and discreet yodelling. The Hill Billies’ other entry is Take Ma Boots Off When Ah Die, which includes the line “I shot a guy in Dallas for beating up his wife”. Did the Hill Billies influence Johnny Cash? They surely did. This song is less nihilistic than Cash’s Folsom Prison Blues, because everything turns out for the best. “Instead of life I got his wife and 16 kiddies too.” And there is Gene Autry singing Buttons and Bows (an Academy Award winning song with a buckboard rhythm from the Bob Hope film Paleface, but made more country when rendered by an actual singing cowboy).

And what of Kitty Kallen singing Little Things Mean A Lot, an absolute heartmelter? It was the number one song of 1954, selling two million copies, but who now talks of Kitty Kallen? She lost her voice at the London Palladium in 1954 and stopped singing live for four years. As part of her therapy she was asked to undress, and that was the end of that.

How about Harry Parry, the Welsh jazz cornettist and band leader, described by some as “Britain’s jazz king”, who died in his Mayfair flat at the age of 44 in October 1956? Or Primo Scala, whose tune Johnny Ragtime is like a cross between Scottish country dance music and Pigbag. Primo was the musical director of the George Formby films, and though he sounds exotic, his real name was Harry Bidgood and he came from West Ham. The Gaucho Tango tunes of Geraldo and his Orchestra are equally transnational, though Geraldo’s real name was Gerald Bright, and he was trained at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Among Geraldo’s later triumphs was Scotlandia, the start-up music of Scottish Television, a deep weave of orchestral tartan.

Some of the music looks forward to the rock ’n’ roll era. Johnnie Ray’s 1954 hit Destiny is an absolute heartbreaker. Frankie Laine’s Rain Rain Rain is a kind of worksong. Ray’s biographer Jonny Whiteside suggested that Laine, Tony Bennett and Johnnie Ray wiped away the bandstand manners of crooners like Frank Sinatra “with a brash vibrancy and a vulgar beat”. And Bennett, whose voice allowed him to surmount any limitations of genre, suggested that Ray was the father of rock ’n’ roll.

All of it was an influence on Elvis, who appears on another of these dusty 78s, singing Blue Moon. Blue Moon is one of my favourite songs. It appears as a motif in one of my favourite films, Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train, as a transmission from beyond, a haunting, and that is exactly how it feels as I play it today.

We’re coming to the Antiques Roadshow bit, where we discuss value, and I say, that’s fine, but I’d never part with them. Some of these records, according to Discogs, might be worth a bit, if I could find an Elvis nut, or a Manchester City fan, who fancied framing the music rather than listening to it. I might even do it myself. But I visited Oxfam this morning, and flicked through the records. They were all in a jumble, pop in with classical, classical with pop. Someone who loved French chanson had donated a load, and I couldn’t help thinking about the circumstances in which these tunes might have rung out, and the sense of romance and joy they would have provoked. I wanted to buy them. I managed to resist. I have my own collection taking up space and gathering dust, waiting for the cull.

Same generation, I think. My dad bought records to play with me, we particularly enjoyed two albums of classic film themes.. when you are five or six you can get enormous pleasure from bouncing round the furniture in time to the theme from Tom Jones, and Colonel Bogeys March from Bridge over the River Kwai. Happiest of happy times.

There's a guy I follow on Instagram who collects copies of No Parlez from charity shops as some kind of art project.