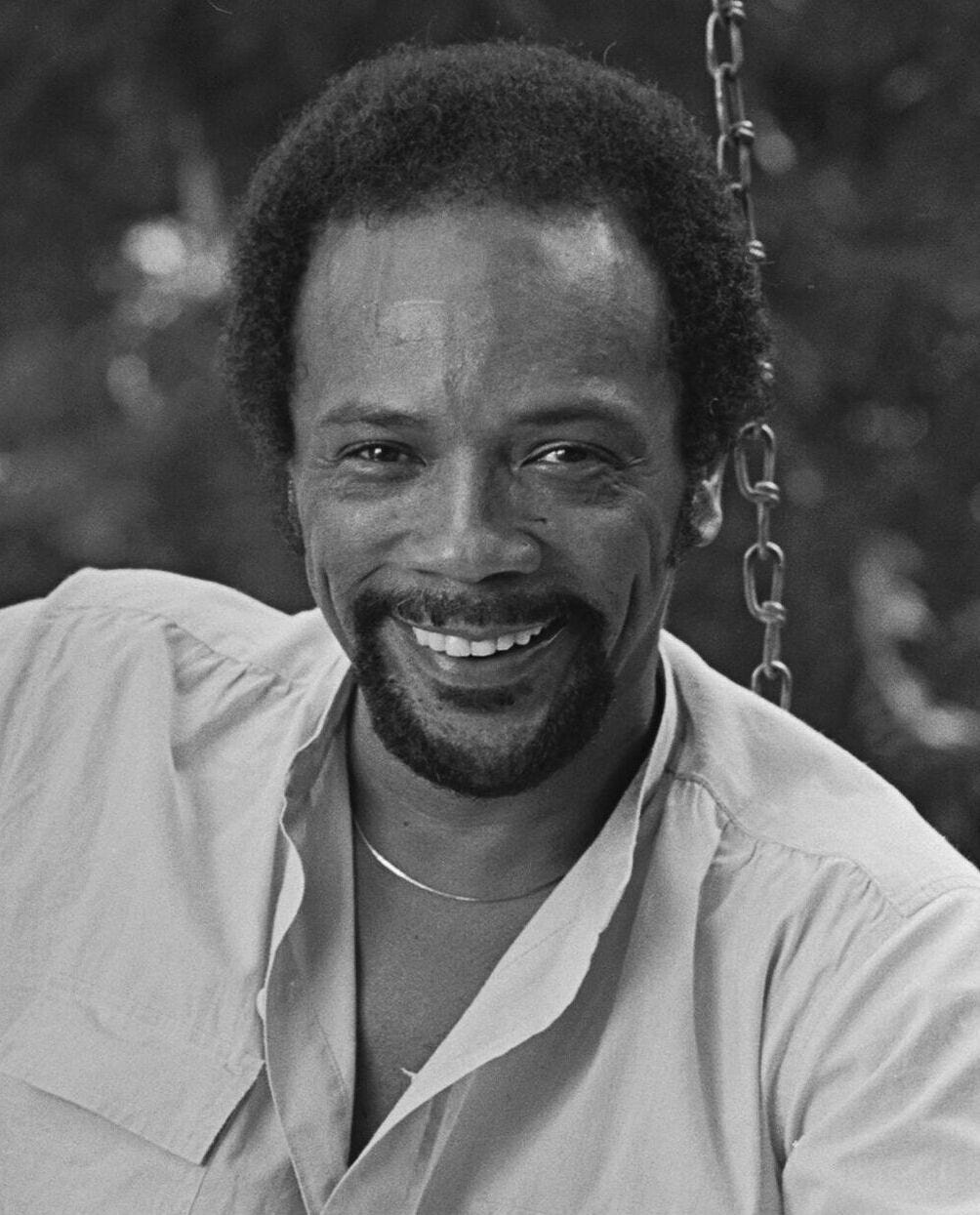

"Pop music is not that big a deal." The musical genius of Quincy Jones

The composer and musician died this week, leaving a rich legacy.

I met Quincy Jones in 1990. He was in Edinburgh for the premiere of Listen Up: The Lives Of Quincy Jones. He hadn’t seen the film, but was curious, and a little apprehensive.

“I did it ‘cause I just came out of a very bad period,” he told me. “It was a spiritual rebirth for me. I felt that I was spiritually strong enough to handle anything. But I still wonder why I opened myself up to this. It’s like people querying your soul, you know? If the film were on you, would you be uptight about it and disturbed?”

“You come out of it all right,” I told him.

“You wouldn’t say I better get the fuck out of town?”

Memory does funny things. On hearing that Jones had died on 3 November at the age of 91, I thought back to the interview, and the way Jones had reacted when I mentioned Michael Jackson. Jones was the producer of Jackson’s most successful (most creative) albums, Off The Wall, Thriller and Bad, records that rearranged the contours of pop music. I asked Jones to calibrate his importance to the sound of Thriller, the biggest selling album in history. What I remembered was the assertiveness of the response. “Listen to all the other records he made,” he said, “and listen to Off The Wall and Thriller, and you can tell.”

At the time, I thought this point was forcefully made. Listening back on cassette it just seems inarguable, though the moment is underscored by the sudden percussion of Jones clapping his hands together. “Michael could do anything,” he said. “You can hear it on the record.”

Back then, Listen Up was framed as a kind of victory lap, exploring Jones’s role in the development of African-American music over 50 years. In the subsequent 34 years, he forgot to slow down. Some of the things he wanted to do never got made - his biopic of Alexander Pushkin, for example. But he kept on working, doing and inspiring.

The music began when Jones was 10 years old, his family moved from Chicago to Seattle. “I guess it could have been incubating - between the lady next door who played stride piano, and going to my grandmother’s house in Louisville. She’d play Duke Ellington’s Mood Indigo, and Earl Hines’s Boogie Woogie St Louis Blues, and blues records like One Black Rat - a lot of silly things. Then I started listening to Louis Jordan.”

In the school band in Seattle, all kinds of music were explored. There was pop, and blues - T-Bone Walker and Eddy Benson. “I always had eclectic taste because I was around all kinds of music.”

He was 14 when he met the 16 year-old Ray Charles, who had just moved from Florida. “We had every job in town. We did everything. We danced. We sang. We played. Told jokes, you know. It was just lovely. And at three o’ clock in the morning we’d go out to the Elks Club and play bebop for free. That was what we really lived for.

“Today, kids act like they’re failures if at 24 they’re not rich and famous. Man, I didn’t even know how to spell rich and famous. That didn’t mean shit to me. My heroes were Basie, Duke, Bird, Fats Navarro, Dizzy Gillespie, you know? That’s where we were lucky. Because all we cared about was getting good. Learning everything and knowing about music. It’s funny, then you get down to a certain era … when you learned how to play music good, people called you slick. You play the right chord changes, everybody says you’re slick. That’s too bad man, took a long time to get there!”

We needn’t go into the full glory of Jones’s career. There are proper obituaries for that. There’s an autobiography and another film. A measure of his eclecticism can be seen from the fact that he signed New Order to his label (“they asked me”), and worked with Frank Sinatra and Count Basie (an introduction that came initially from Ava Gardner). “We had a good time,” Jones said. “I never had any problem with Frank.”

I mentioned a quote from Miles Davis, who said something to the effect that “when people say pop music, they mean white music.” Jones laughed at that, and told a story about his first number one as a producer, It’s My Party. It happened not long after he was hired as vice president of A&R at Mercury Records. “Lesley Gore was the first pop record I ever made. It was a dare. People kept saying ‘You guys are beboppers, you’re budget busters’. I said, ‘Pop music is not that big a deal. It’s much harder to play jazz, musically.’” Someone called Jones’s bluff, and challenged him, saying: “So why don’t you do it?”

“We were at a meeting in Chicago. They were throwing demos around and I heard this 16 year-old girl, her voice was in tune, and she had a pretty nice sound. I found the song for her. Three weeks later, we had a number one record.”

It’s My Party is one of the great pop hits of the 1960s, but it didn’t make Jones rich. “I didn’t know producers got paid. Nobody told me. I was working for fun, I thought that was part of the job. I never got paid from that. Not a cent.”

Ultimately, he left his desk job to get into the business of film soundtracks. “I think at the time they offered me a million dollars to stay 20 years,” he said. “And that was a lot of money. But I knew I didn’t want to do it. I quit the job. And I got divorced. I wanted to write for movies. I went to Hollywood and I had no money. I just took a chance. Because I didn’t want to do that for ... it felt like the rest of my life.”

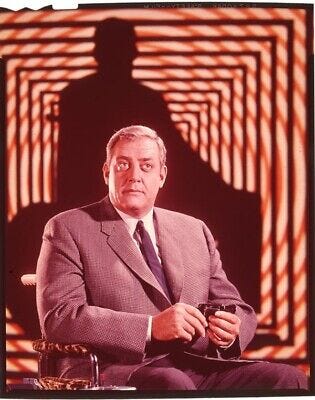

Jones was involved with numerous notable soundtracks, to The Pawnbroker, In The Heat of the Night, The Italian Job, the TV adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots. I asked about his contribution to the great 1960s’ drama Ironside, starring Raymond Burr. Jones wrote the score, doing the pilot and eight episodes. (The music appeared later in Tarantino’s Kill Bill: Vol 1, its futuristic allure now remoulded as retro chic).

“That was the first synthesiser,” Jones said. “Paul Beaver was like The Godfather of electronic music. He had this crazy house. And it was like a Frankenstein laboratory. Dave Grusin and Johnny Mandel and myself, we all used to go out there to find new sounds for movies. And he said: here’s a new instrument, the Fender Rhodes. Nobody heard it before, record people, nobody, until Dusty Springfield did it on Brand New Me. They had a Novachord, that had altered pitch, he had a clavinet. He had a thing called the Canary. He used the contrasbass clarinet. Great colours, you know. I always love colours. So I said: ‘I need something like this’. They said: ‘Try this’. I used it for the siren in Ironside, then I took it back and said: ‘What else you got, Paul?’ He said: ‘Here’s the synthesiser’. I said: ‘I already used that’. He said: ‘You don’t understand. This thing has 40 million possibilities.’ He taught us how to use it. He said: ‘You have to learn it because it’s the future,’ and he was right.”

This was in 1964, but it wasn’t Jones’s first musical revolution. “It was the same with the first electric bass in 1953. With Lionel Hampton and Monk Montgomery. When they first came over to Europe… Leo Fender came down to the plane, and gave Monk Montgomery - Wes Montgomery’s brother - his instrument. And he cried out: ‘This motherfuckin’ thing’s not going to work!’ And that instrument, the guitar, was the motor of rock’n’roll. So you see that evolution building up. In retrospect, it’s interesting.”

“You’re obviously not precious about using ‘proper’ instruments,” I said.

“No,” said Quincy Jones. “I don’t believe in purity. That’s bullshit. If it works, it works.”

What a lovely article! Thank you so much