Poetry. Full Stop.

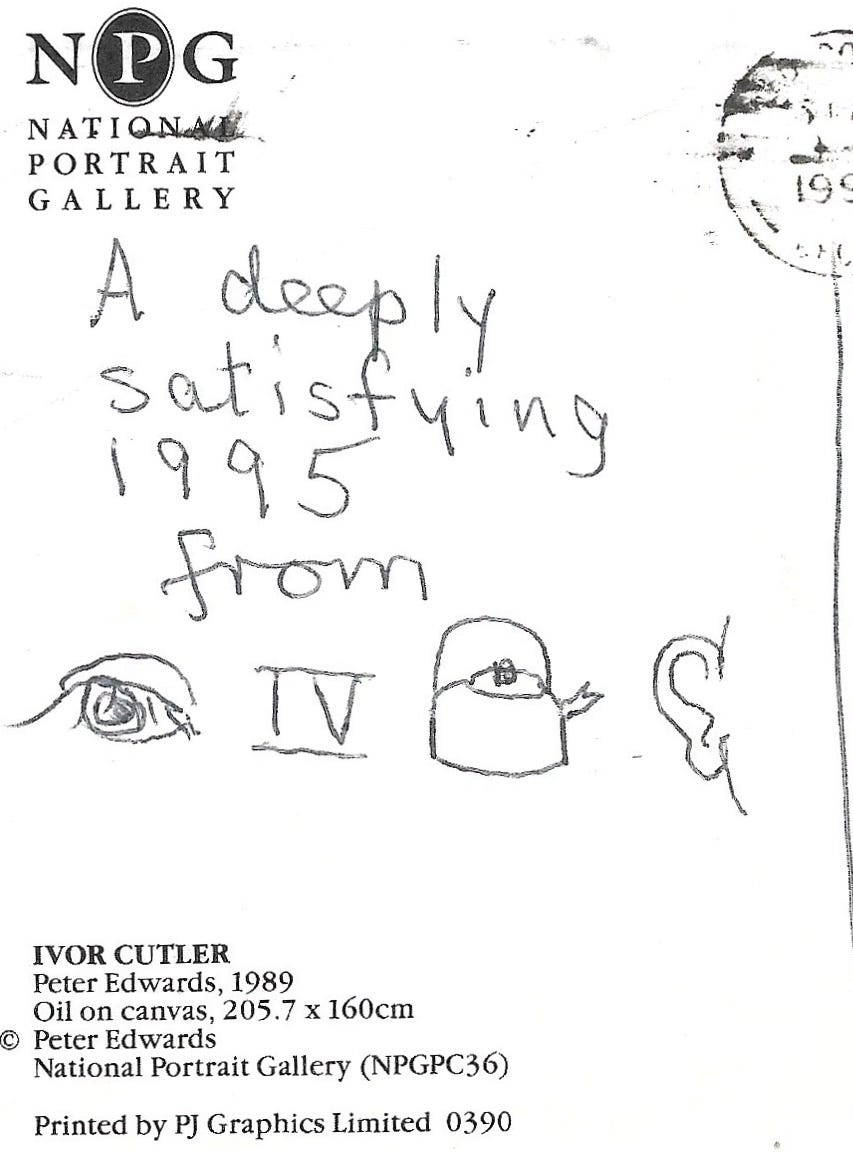

On the occasion of his 102nd birthday, a hirple through the poetic humour of Mr Ivor Cutler, humorist, teacher, cloud-fancier, opsimath

I go to interview Ivor Cutler at his house. Mr Cutler is a humorist from Glasgow, and a cult figure on the John Peel Show. His comic vignettes are as sad as they are funny. They are very funny.

I meet him at his flat in Dartmouth Park, London.

It is a small flat. The living room hosts a harmonium and a large photographic print of Mr Cutler in his younger days, looking like Bernard Bresslaw from the Carry On films, when in fact, Mr Cutler is actually Buster Bloodvessel, the courier in The Beatles’ film A Magical Mystery Tour. Some people say that Buster Bloodvessel is a bus conductor, but that seems like a demotion.

There are some preliminaries.

Mr Cutler disappears to make coffee.

From inside the kitchenette I hear his tremulous voice.

“Can you handle soya milk?” he asks.

“Yes,” I say.

“You look as if you could handle anything,” he says. “Except pleasure.”

That’s the Ivor Cutler story I told in Alternatives To Valium, and it’s all true. I could have added the bit where he examined me closely before announcing. “You don’t look like a newspaperman. You have fighter pilot eyes.” I don’t think anyone has ever said anything nicer to me in my life, and even then, I’m not entirely sure it was a compliment. Fighter pilot eyes, as we shall see, were something that Ivor did not have, and it proved a handicap in the Second World War.

Why Ivor? Why now? Well, because. I meant to write this for what would have been Mr Cutler’s 100th birthday, on 15 January 2022, but didn’t get round to it. I’m sure Ivor was punctual by nature, he was certainly punctilious, but there’s something appropriate about being two years late to the party. It’s almost as good as not being invited in the first place. Also, there wasn’t a clamour.

I think about Ivor all the time. My daily hirples take me past his old flat on Laurier Road, and I always wonder about the how and why of commemorative plaques. Vivian Stanshall of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band has one on his old flat in Muswell Hill, and he’s no more or less obscure. But Ivor only died in 2006, which - now that time appears to be jet-propelled - feels like yesterday. It’s early yet.

Why Ivor? Why then? Long story. To those who knew about him, Ivor Cutler was an enthusiasm. He was, as he took great pride in telling me, one of Peel’s most frequent guests, second only to The Fall. There is, if you have the time, a kind of symmetry there. Ivor and Mark E Smith of the Fall both exist in singular universes full of mottled language and jagged juxtapositions. They are originals and outsiders, consistent only to their own logic.

But, och, I’m boring myself. I loved Ivor, loved the twisted misery of his Scotch Sitting Room Tales, his Jungle Tips, Fremsley, Creamy Pumpkins, the whole lot. Think about Gruts For Tea, and you’re transported immediately to a parched landscape somewhere between Samuel Beckett and …

Cripes, I’m doing it again. The thing is, I worked for Scotland on Sunday magazine. It was a monthly magazine in a weekly newspaper. After a ferocious negotiation in which Mr Cutler asked for far too much money, and was given it, he agreed to contribute a monthly item. Usually, it involved some words and a naive drawing. Sometimes the words had the coherence of a very short story. Mostly they didn’t. This strangeness went on for a while, because nobody cared what happened in the magazine as long as the adverts for conservatories kept coming. Then someone noticed, and Ivor’s contribution was cancelled. He kept in touch, sending occasional letters stuffed with surreal “stickies”, and when the photographer Katrina Lithgow collaborated with him on a book of photographs, Ivor, with some reluctance, agreed to an interview. True, he did ask me twice, at considerable length, to explain the circumstances which had led to the cancellation of his monthly item, and this interrogation did require me to describe the physical characteristics - hair style (“combed to the side?”) and accent (“English?”) - of the editors who had wronged him, but he soon warmed up.

We talked at first about the photography book. It was titled A Stuggy Pren. A Stuggy Pren was also one of his poetic contributions to Scotland on Sunday. It was published in 1993. Could you call it a poem? I think so.

This is it.

A pren, a stuggy pren

leezin and bloozin

and soggilin at a

fleepy klodge

My slerky chits

a beezy woop and

snoped a zoop.

Try getting that past your spellcheck, never mind your editor.

When we talked on the telephone, Ivor suggested he had some thoughts about modern poetry. That’s where we started. Modern poetry? “Well,” said Ivor. “Poetry full stop.”

Short story long. In the beginning, Ivor considered poetry to be a “top of the tree communicator”. But as time went on, he became increasingly dissatisfied and puzzled. “And when I started writing poetry myself I discovered I was hopeless.”

Ivor said the poetry he wrote in his early thirties was “absolutely rubbish. I’ve kept it to keep me humble.

“When I started, I decided to write nonsense poetry. That’s to say, just using words and listening to the sound that the words made, rather than their meaning. I did that for about six years, and then gradually I started bringing proper words in, until eventually it was all okay-type words, but the music of the words was there.”

He digressed for a bit. First, perhaps reflecting his status as a member of the Noise Abatement Society, he suggested that the nervous squeaking of my chair might interfere with the recording. Then he said that his early attempts at poetry were hindered by the fact that he already had “some reputation”, because he had appeared regularly on a radio programme called Monday Night At Home, in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

“Because telly hadn’t got a grip,” he said, “people would listen to the radio. I was quite controversial, which was good, of course. In the Radio Times somebody was foolish enough to say, ‘Ivor Cutler’s work makes my wife’s hair stand on end, get rid of him.’ And then the legions sprang to the defence. The other side came in, and to and fro until the editor said, ‘This must now stop. Or cease’. But of course, it was very good for my reputation.”

Where were we? Yes, poetry, full stop.

“I used to go down to Compendium Books in Camden Town and I would look at their poetry list, and I would just say, ‘it’s boring’. I’d more or less given up poetry. But a couple of years ago, I went in and I thought ‘I’ll have another shot’. There was a poetry table, I looked through it and it was the same old stuff. As I left, I noticed there was one book in the corner that I hadn’t picked up. And I thought, ‘Och, be fair’. I picked it up and it was a book by John Burnside. I opened it, and immediately somebody was talking to me. Communicating with me. And I started to cry, because it was too much. I suddenly realised that for all the 30 odd years that I’d concerned myself with poetry no one had ever fed me before. Of course it was traumatic. I went to the publisher, and they said ‘He’s a difficult kind of bloke’. I said, ‘I’ll write to him, care of you.’ Which I did, and hearing he was a Scot I offered him a Forfar bridie if he came round. He comes from Dunfermline, which is near enough. He was taken with that, and he came round. And we got on like a house on fire.

“We understood one another about communication. He rubber-stamped it for me, really. Which is, instead of using the intellect to understand the words of a poem ... something comes from my unconscious mind and goes to the reader or the listener’s unconscious mind. I don’t know what I’ve communicated. They don’t know what they’ve received, but they feel that they’ve been communicated with, and they feel the happier for that, because it gets into their unconscious and deals with the stuff that’s already there, and it perhaps ties things together. I suppose one could say it’s therapeutic. The words that I write are just a way of opening, of allowing the meaning from my unconscious to go in, so the barriers go down. So, the nicer the music, the more easily acceptable. And that’s how I see poetry.”

Ivor said he was not a fan of literary criticism. In fact, when asked by a magazine to compile a list of things he hated, he put “lit crit” at number one. “Me being controversial,” he said. “I realise now it was because 50% of people come to words intellectually and try to understand the words with their brains. Poetry, for me, should not be approached in such a fashion, with all these clever references to obscure books and so on that only the cognoscenti will know about. That’s not poetry.”

We talked for a while - or rather, I listened - until I noticed that a look of concern had crept across Ivor’s features. “You’re listening to what I’ve been saying,” he said. “And I don’t know whether there was any empathy in you for it.”

“I agree with you,” I said, a little too quickly.

“Oh, you agree?”Ivor said suspiciously. “Wow. I’m delighted to hear it.”

At this point, Ivor proposed that instead of a regular interview, we might conduct an impromptu poetry session, with me avoiding my intellect and him reading out the results. “It might bring a je ne sais quoi to the interview,” he suggested.

Imagining the reaction of my editor when I filed 1800 words of my own nonsense verse, I tried to divert Ivor’s attention.

“Maybe we could talk about what it was that you hoped to do when you first started out.”

“You mean when I started being publicly creative?” said Ivor. “That’s simple enough. If you look to the wall there, to these paintings, particularly that green one in the middle above the mirror. I was a Sunday artist, and I wanted to be a full time artist, but I was a teacher and had a wife and two kids, and so I couldn’t.”

An art teacher?

“No, no. I wanted to be a painter, and I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll write funny songs, and people will sing them, and I’ll collect the royalty, and then I can leave teaching.’ So I wrote a lot of funny songs. And I went round Tin Pan Alley for a couple of years trying to flog them. Eventually, somebody took an interest. He got people along to have a listen to them, including Ned Sherrin, and Ned, bless him, was on a thing called Tonight, on the telly, and they put me on.

“He said, ‘I’ll have you on for a week’. We did the first night. There was a three verse song. In the middle verse, the engineer switched the sound off by mistake so they had to gave me a second night. But the guy in charge said, ‘This guy’s ahead of his time. We can’t. Enough is enough.’ Then Monday Night At Home, the radio show, was starting, and we got the producer along to hear me. He listened, and his face was blank, and he said, ‘Is there anything else you do?’ I said, ‘Well, I write poetry, stories.’ And he said, ‘Well, if you get some stories, get in touch.’

“I hadn’t written anything since I was 15, but I went home and I lay on the bed and I had a tape recorder, the big reel to reel thing I’d just bought, and I spoke, and out came a story. And I thought, ‘Oh! I’ll have another shot,’ and they just came out, easy as pie. I did three of them, then I wrote them down on the paper and went off to BBC, and the guy said, ‘Oh, well, thank you.’ And I said, ‘But could I read them out myself?’ He went in behind the glass thingy and I read it out and his secretary came out and said, ‘I think you’ve hit the gold mine, Mr. Cutler.’

“It turned out to be a copper mine. That’s how I got started. I wasn’t making enough money to leave teaching. I did cut my teaching down to three days a week, which was something, but I was enjoying working with children so much. Also, they served to keep me humble. Because, you know, if you’re on sort of an ego trip all the time, it’s not very good for you. And I got a lot of kicks out of kids because I started to specialise in drama and movement.”

Ivor talked at length about his teaching methods, and it was fascinating as he said it, and even now - 31 years later - as I listen to the tape. But there is a thing about Ivor’s anecdotes, even when they are factual, and that is that they are best received, as Ivor understood, in his own voice. What is notable, and relevant to the work, is the way Ivor talked about teaching six and seven year old children how to “get rid of their shyness and their guilt feelings”, and his sheer joy in seeing their happiness as they began to conquer their limitations.

Picture the scene. A classroom of infants being taught by Ivor Cutler. (Or rather, Mr Cutler. Ivor, ever the school teacher, liked strangers to call him Mr Cutler until he knew them better.)

“Of course, the kids would go home and tell their folks what went on,” Ivor said. “And parents would occasionally come up to the school and complain. The kids, of course, when they found out the parents were reacting that way, they’d keep it to themselves because they didn’t want the enjoyment spoiled.” Some of the parents at this school - the Fox in Notting Hill Gate - were more understanding. One of them, the film director Ken Russell, asked Ivor to write some music for a TV project, and offered him a role in a film. “I got a heart attack just at that time, so I was unable to oblige him. Just as well, because I’m absolutely hopeless at remembering things, and when I perform, I always have the words bang in front of me.”

“What was your own childhood like?” I asked, suggesting that much of his work paints a very vivid , not to say Spartan, picture of childhood.

“Oh,” said Ivor. “Could I, before I leave this subject..? I discovered that doing the things that I have done creatively, besides painting, it’s all the same thing. I see creativity as a therapy, and I found that in fact, I was reaching many more people by using words than I was with paint. So in the end, I kept the whole lot going.”

Even now, with all the tiles on the board, it’s hard to describe what it was that Ivor Cutler did. Keeping the whole lot going meant he wasn’t a straightforward anything. He was a funny kind of poet, not a comedian, a songwriter of sorts, a wonky storyteller. But his work doesn’t transfer easily. Anyone else singing his songs risks sounding daft. The stories need his voice. His doodles are just that.

Perhaps we should take the hint and think of him as a teacher: Mr Cutler. A lot of Ivor’s conversation was about teaching, a lot of it was about learning lessons in childhood. In concert, and even on his radio sessions, Ivor’s delivery was formal, precise, remote, even when it was excruciating in its intimacy. He was, in at least a couple of senses of the word, masterly. Keeping the whole lot going meant keeping control of the room. I remember seeing him performing on the Edinburgh Fringe, and him voicing his disappointment at latecomers as they tried to find a seat. There was nervous laughter, but Mr Cutler wasn’t joking. If he could have dished out detention, he would have.

Ivor didn’t set out to be a teacher, but he understood the fragility of childhood. His approach to everything was influenced by his experience as a pupil.

“There’s a guy in Scotland that strapped me 200 times over three years for bad writing,” Ivor said. Strapping, or belting, was commonplace in Scottish schools until 1982, and corporal punishment wasn’t fully illegal until 1987. “It wasn’t until I went to Jordanhill to become a teacher that I discovered that the reason my writing was bad was because there’s a sheath made of stuff called myelin, which covers the nerves in the body, but it doesn’t do it right away, which is why little kids don’t have much coordination. Once the sheath’s around the nerves, you get coordination, but with writing, it can take up to about 13 years old, and I was getting strapped because of my nerves weren’t myelinated.”

“That sounds brutal,” I said.

Ivor released an involuntary sigh. “I think he was a bit of a racist. I’m a Jew, and he used to have me come out and sing the Jewish national anthem. He’d say come on out and and sing Call Out The Lifeboats, which was the nearest he could get to Kol od ba’le’vav, which is the beginning of Hatikvah. Looking back, it seems funny, but when I put it all together, you know? I met him when I was about 18, out in the street, and I realised why he was so bitter, because he was a wee bauchle of a man. He was much smaller than I was, and he’d obviously chosen to work with junior children because they were smaller than him.”

Isadore (Ivor) Cutler was born on 15 January, 1923 in Ibrox, Glasgow, “beside the [Rangers] football ground”. He started school there, and continued in Shawlands. His mother Pauline brought up the children, and his father Jack was a manufacturer’s agent.

“I used to be ashamed of that, because, in a sense, he’s a middleman between the manufacturer and the shopkeeper. He’s taking his percentage for carrying something from one person to another. I used to think that’s no way to earn a living.

“Then I read something by Ernest Benn about capitalism in which he said that the life blood of commerce is the middle man. This was as an adult, and I thought, ‘Crumbs, my dad was doing a good thing after all, by helping in the distribution of goods, the way business was constructed in those days’. That made it okay, except I was no good at it, because my dad wanted me in the business, and I couldn’t. It’s not my kind of thing. Not only that, it was during the war and the goods that were available, understandably, were of very poor quality, and I had no faith in what I was asked to sell. So I decided on teaching.”

Ivor summarised his career as “30 years as a teacher, and 30 odd years as a humanist”. But before he got to that point, he had to navigate the war.

“It’s amusing,” Ivor said. “Well, bitter amusing. When the war started, I wanted to be a doctor, and I’d been accepted for training. My dad didn’t want me to be a doctor because my two brothers were going to be doctors, and they wanted at least one bloke to be in the business, which I didn’t want to be. I was a humanitarian vegetarian at the time.” He laughed. “Pathetic. Oh, God, such a pain in the ... I wouldn’t sit down to the table if anyone was eating meat, you know, teenagers. So my dad said to me, ‘Look, if you become a doctor, you’re gonna have to get hold of a frog and smash its head against the wall like the Nazis did with babies, and then dip it into a bath of acid, and it will try and wipe the acid off.’

“I got the message and said, ‘All right, I’m going to become a journeyman and go to Russia,’ you know, brothers of the world. So I went and joined Rolls-Royce and became an apprentice fitter, and I discovered I was no good as an engineer, because although I loved the aesthetics of mechanical engineering, I made one or two boo-boos.

“I knew that the only way I could get out of Rolls-Royce was to join the Air Force as a navigator or a pilot. Because of my Highers, I thought ‘Pilot? that’s just like driving a bus.’ I had no respect for that. I thought, navigator, because I was good at maths, that’s more my style.

“So I went and enlisted as a navigator, went through the whole training, but they were a bit worried about my flight plans. On my last flight before I got my wings, they sent a couple of guys up with me who said ‘we would like to take some photos, OK if we’d come on the plane?’ I said, 'Yeah, plenty of room for all’.

“What I didn’t know was they were out to watch me see what I did. So the plane got up, and there’s a thing you can move about that you fix so that it’s going the same direction as the ground is rushing along. I sort of got that right. Then I looked up and I saw some clouds, and they were beautiful. We were up about 10,000 feet. Oh these clouds! I had a good look at them, and then I thought, ‘Oh crumbs, I’ve got other things to do’.

“And of course, these guys realised why my plots were not as they should be. The following morning I went up before the CO and he said, ‘airmen are expendable, but not aircraft’. I was grounded.”

Before Ivor was sent back to civvy street, he was offered the chance to muster for another military role. He expressed an interest in radio navigation, bouncing echoes off radar, but was offered the chance to become a rear gunner in a plane.

“I said: ‘A rear gunner? Shooting people?’” He laughed. “I’d have been doing daylight raids in Mosquitoes to Berlin dropping bombs, but using the machine gun, and my aircraft recognition was impossible. I knew that by the time I’d worked out whether it was an enemy or a friend, that’d be me.

“And not only that, I was insulted. There’s a Jewish joke about when the Czar enlisted the Jews into the army to fight Austria, they discovered that the Jews were absolutely fantastic at sharp shooting. So they made a regiment of them, and sent them off to the war. And the officer saw the enemy, and he said, ‘Right, fire.’ And nobody fired. He said ‘Fire, you stupid bloody …’ You know. And he said, ‘Why are you not firing?’ And one of them said to him, ‘There’s people there.’

“And that made me proud to be a Jew. That was my war experience. I was deeply embarrassed at the time, but with hindsight, I think the almighty must have had it in mind for me to do something rather more important than getting shot to pieces.”

“What was your childhood like?” I asked again. “Apart from the belting? Or was that it?”

Ivor laughed. “No, it’s not, actually, I don’t know how to describe it. I’m afraid you’ll have to ask me more direct questions.”

“If we were to take Life In A Scotch Sitting Room…”

“No, forget about that. That really is an amalgam of my experience of Scottish life as I saw it, plus parts of my own life. It’s not really an accurate kind of thing. The Glasgow Dreamer book has more of my life in it. But I can’t leave these things alone. I have to muck about with them a bit to make them palatable. People have asked me if they could do my biography, and I’ve always turned them down, because the idea of having to dredge in among that stuff would bring back a lot of painful memories. You know, when you go for psychotherapy and you sort of dredge it all up, and you get very, very depressed? I don’t really want to do that myself. So, ‘By his work, shall you know him’ seems to me a much better way of doing things.”

“You talk about therapy, and how there’s pain that you don’t want to dredge up. It doesn’t seem very cheery.”

“Oh,” said Ivor, allowing himself a little laugh. “Ha! When I was 15, I tried to commit suicide.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. Well, I’ll put it in its context. My big brother was a medical student and he brought home a sample of aspirin with a packet with six. I saw it kicking around. I looked at it and it said, ‘Maximum dose, two.’ So one night, I went and took the whole six, and then I wrote a goodbye letter.”

Ivor laughed harder this time, releasing a noise that sounded like a hyena deflating a balloon. “I thought that should do it, you know? And I wrote, as I remember, I had just discovered what a horrible place the world is. This was the mid-1930s when Hitler was doing his thing. But not only that, just the torture of being a teenager.

“I woke up all refreshed the following morning, and foolishly I said to my brother: ‘You know these aspirin? I took them all and I tried to kill myself,’ and his face went ‘Oh’. He went and told my mum and dad and they were deeply embarrassed. What can you do with a teenage son behaving like this? They just decided to treat me with kid gloves for a bit, but I never took advantage. I think I was quite nice about it, and the thing just passed over.”

“But did you fully expect to die?”

“Oh, yeah, sure, I was stupid” He laughed. “And suicide has always been a good friend to me. It is, for me, something very comforting. The notion that it’s available, and also the notion that it’s extremely difficult without doing yourself an injury to actually make an irrevocable death by yourself, because the options are really not very pleasant. High buildings has been my favourite for quite a time. But recently I was in a building, and it was up about eight storeys. I could quite easily have jumped onto the tarmac below. And because I’ve got the two sides of me working on it, I decided against it, because I have discovered that at times of great despair, it’s usually been a preamble to exciting things happening. So I’ve hung on. Like when my marriage broke up, I thought I was old and ugly because I was what, 40? So life was to all intents, over. And in fact, life began then, as I discovered.”

We talked a little about life after divorce, and Ivor contrived to reveal almost nothing, except to say that in the aftermath of his marital split he discovered that people related to him differently, and it gave him some self-respect. He mentioned his two children, saying only that he saw them “now and again” and they were living in London and seemed to be doing things that they wanted to do. “I’m quite pleased with them,” he said, swallowing his words. “Sorry,” he continued, “talking in this choked way. It’s a bit emotional for me.”

“If you feel I’m prying too much, just tell me,” I said.

“No,” Ivor replied, with a high-pitched laugh. “I’m astonished at your cunning. I love standing outside myself and watching what I’m doing. The thing about you working on me - you’re concentrating on that, and what you might perhaps tend to forget, is that I’m busy concentrating on you at the same time.”

“Tell me more about the desire to write things.”

“Oh, creativity. Ah, glad you’ve brought that up, because my intellect really gave me a very tough time on creativity. At 15, I decided I wanted to be a concert pianist, and my dad, bless him, managed to get hold of a piano. I got started. And then I’d get a block, which is like the intellect saying you’re just being stupid, you’re no good. Around that time I’d started drawing, and so I left the piano and went and did the drawing. That was okay. Then a block came down, and I went back to the piano, and it was okay, the block had gone. But eventually it came back and then went back the drawing, and I discovered that I could keep one ahead of the intellect. It was borne in on me that the more options I had, the easier it might be. So every time I started something new, the snowball effect. If you can do a couple of things, it’s easier to take on a third and so on. I was counting up the other day about how many, many things I did. It’s about 13. Well, I suppose writing songs and poetry would come first equal.”

Ivor told me he had been lying in bed the previous night, playing around with Pitman’s shorthand. Usually, he said, he kept Japanese and Chinese dictionaries around his bed, because he was fascinated by the idea that little black marks on paper could communicate. It was a strange digression, not quite coherent, which brought to mind (in Ivor’s mind) an old film in which a woman - “the hapless maiden” - caused a man to die of shock by telling him that she has poisoned his coffee. “Suppose she had said to him ’I poisoned your coffee’ in Chinese. He’d choke her to death.”

I must have looked baffled, because I was. “It was just,” Ivor said, “I mean, what are these noises? Just some vibrations in the air, and that killed him. It’s more or less that. Which is why, when I’m creative, I never know what I’m going to do, because otherwise there’d be no fun..”

I became suddenly aware of another presence in the room. It was a tartan elephant. Not Elmer or Babar. The elephant was Scottishness. “Nationalism is an infantile disease,” Ivor said crisply. “It is the measles of mankind - Albert Einstein, I’m getting that made into a sticky label.”

“Do you feel that strongly yourself?”

“Oh, sorry,” said Ivor. “The nationalism. Of course, I’m a Scot by birth, and I’ve taken on a lot from my Scottish environment.”

He paused for a moment, and mentioned how the Jewish part of him had “diminished to nil” because religion was irrelevant to his life, “except I know I have to stand up and be counted.”

“You’ve lived in London a long time.”

“Well, I’d 28 years in Scotland. Everyone in Scotland thought I was daft, my parents and my family and my colleagues, everyone.”

“Daft in what way?”

“I mind when I started. ‘I mind!’ - the Scottishness is getting to me. I mind when I wrote my first song on the piano at home and I said, ‘Mammy, come and listen to this song’. She said, ‘All right’. I sang the song through to her, and I could see her face drooping a bit. And she said, ’It’s very nice’. And then she couldn’t help it, she said ‘Ivor, couldn’t you write something nice?’ I did a song about ‘I’ve a hole in my head, dentist/please, from the top of the teeth/put one set in the top, dentist/and another set underneath.

“You know, daft stuff.”

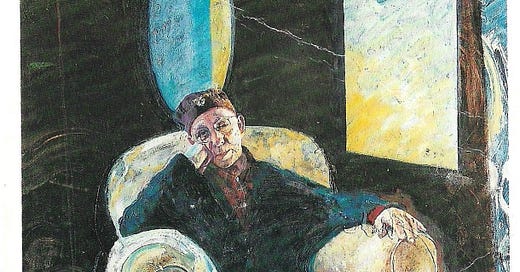

Ivor pointed to a picture on the wall, of a man’s face.

“He looks a bit troubled,” I said.

“Is that how you see it? I’ve said to people I’m interested in their faces, looking for some kind of understanding, and then I just play around with the face and doodle. And that word ‘doodle’ is a derogatory type of term. But in fact, creativity is doodling. If you’re a good doodler, and you have a mead of craftsmanship along with it, then you turn out a good product. Doodling is not to be sneered at. It’s the beginning of the stuff.”

“Did you think your creativity was sneered at?”

“Back in Scotland? My creativity was sneered at, yeah. I remember doing one of these faces, and I stuck it up in the staff room wall while teaching in Paisley South school. When I was out the room, somebody got a Polo mint, licked it and stuck it over one eye, making it into 3D.” Ivor laughed at the memory. “And he was a really nice, warm man. He taught woodwork to the kids. But he was fairly middle of the road, I suppose. There was no malice. He just found it amusing, daft, and so he added his two cents.”

In Scotland, Ivor said, “everyone was very free with the word ‘no’, and ‘that’s stupid’, and ‘can’t you do something sensible?’ I was working with my instincts, and I went to Glasgow art school evening classes, and I drove the teacher nuts. I was working with clay. I would do, you know, the equivalent of the picture I showed you. The teacher eventually went to Benno Schotz, who was the head of sculpture, and said, ‘get rid of this bloke’. Benno Schotz asked me to come and see him, and he said, ’Why don’t you take a studio in town, Mr. Cutler?’ I said, ‘Well, I like it here, because it’s all the interchange between the students.’ He was a nice man. And he said, ‘Well, I can understand,’ and that was it.

“But ... oh crumbs. I was doing appreciation of art there. And the picture the man wanted to use that week wasn’t there, so he turned to the class and said, ‘has anybody any drawings or paintings with them that we can discuss?’ I took out my book, and I remember one of the eyes had teeth in it instead of an eye. He put it up on the easel, and he got so angry, and he really slated it. I could feel all the people suffering with me. It was a very nasty thing. And I mean, he could paint himself, but it was your proper, regular Scottish landscape, stuff that looked like things, no nonsense. And I thought, ‘I don’t think Scotland is where I should be’.”

Ivor applied to teach at AS Neill’s iconoclastic boarding school Summerhill, in Suffolk. He felt he had to stop teaching in Paisley, because his reluctance to use the strap was giving him a nervous breakdown. “They thought I was a softie,” he said.

“In the end, actually, I bought a belt. I sent off to Lochgelly, where they made them, and I got a thing about this thick. I thought, I can’t use this on children. So I went to the staff room and said, ‘has anybody got a skinny belt, and I’ll give them this fat one?’ There was one teacher, a real sadist, and he made the exchange, and I got this thin one. I got into the classroom, and I hung it up on a nail on the wall and I looked round at the class.

“Of course, they had to test me. And I hit them. They were lovely kids. When I came down to London eventually to teach, I really missed the Scottish kids, they had a quality of directness and they looked you in the eye: if they did something, they owned up. They were wholesome.”

Ivor’s application to Summerhill was accepted. He knew AS Neill’s work, and the school had a vacancy. Before he left Paisley, he sacrificed the strap. “I got a razor blade. I said, ‘Right, I’m leaving the school.’ I cut it into 50 bits because there were 50 in the class. I gave each kid a bit, so they could think, ‘Thus are the mighty fallen’. I loved that moment.

“I went off to Summerhill for a couple of years, and then down to London, so I could go to art schools and perhaps find a woman, because it wasn’t easy out in the country. I’m not very good in the country, because I don’t know what to talk about to people, like crops or animals or stuff. I’m a townie.”

Ivor’s time at Summerhill wasn’t without incident. He began by following the principles of the school, “which was very foolish, but I was a young man, 28. The head called me in, she said ‘Mr. Cutler, I hear you’ve been rewarding the naughty children.’ You know, I was just embarrassed. How am I going to explain to this woman? But you know the school diaries that you write up? I said to the kids, ‘A diary is personal. You don’t need to show me your diary ever, but if you want to, I’d be delighted to see it.’ Of course, virtually all of them didn’t show it to me, and when I left that school, a big heavy fella took over. I heard this afterwards: he said, ‘Right, diaries, let’s see what you’ve been doing.’ He blew a gasket, but the kids must have been frightened out of their wits.”

Ivor recalled another incident at Summerhill, where he was teaching the nine times table and, noticing that some of the children were having difficulty, found himself saying he could do it standing on his head. “Then I realised what I’d said. So I put a cushion on the floor and went over onto my head. All my money fell out my troosers, so I came down sharpish, and the kids pretended they were stealing it. I had a theory, because I remembered: in Shawlands there was woman who had a wart with a hair coming out of it. And I thought, the more things like that, hooks for memory that I give them, the better it will be.”

It’s obvious now, and should have been obvious then, that Ivor Cutler never stopped being a teacher. His subject was hard to define, but perhaps it was everything - the whole bridie - and he approached it with a series of prompts about innocence, which he was in favour of, and disappointment (less keen). He cited the story of the Emperor’s New Clothes, a tale in which “the little boy, children, see through all the guff”. But more broadly, his project seemed to be defined by an adult’s decision - his decision - to swerve and defuse the disappointments of adult life. I didn’t say this to Ivor, and I can picture him now, replying ‘Oh, is that what you think’, as I swivel on an uneasy chair.

Ivor cited a French philosopher, whose name escaped him. I’m going to guess Henri Bergson, because I have Google, and Ivor didn’t. This philosopher, Ivor explained, “said incongruity is the basis of laughter, and he handed it to me on a plate just at the right moment. It’s been my stock-in-trade. In a way, it’s the equivalent of the wee boy and that story, The Emperor’s New Clothes.

“There are, of course, frustrated children. I don’t mean necessarily children. I mean people like yourself. I mean, I’m a child, still, I don’t see any hope of changing. I’m very grateful for that, and I think it’s people who still have the capacity to see through rubbish that find me to their taste provided they don’t try and intellectualise and puzzle it all out, and say ‘this is all very profound, and what’s the real meaning? That’s stupid.’”

I think, perhaps, this was a warning not to delve too deeply into the mechanics of Ivor’s work, or to seek answers in his life. He obviously liked the attention, but on his terms. But incongruity can be a complicated thing, especially when it juxtaposes laughter and sadness, as Ivor was wont to do.

“I never know what I’m going to do,” Ivor said. “Otherwise, it’d be no fun. It’d be like going up the M1. What I do is like a ball of wool. You get hold of the first couple of inches from it and try and pull it very gently so that it doesn’t fankle. Then in the end, I snap it and I get to the bottom of the page.”

But yes, incongruity. I wondered aloud, imagining Ivor pulling on his ball of wool, whether his humour drew from a deeper reservoir of sadness.

“So, well,” said Ivor, “I think that’s par for the course. If you think of … who’s the guy that did himself in? Tony Hancock. All the humorists I’ve met have been miserable men.

“All the good ones, I would say, are like that, because they’re basically serious men and concerned men. They’re deeply unhappy and they’ve found them a way to be which perhaps allows them to live with themselves, or to put on a good face.”

“Are you quite troubled still? I mean, are you tormented by things?”

Ivor sighed. “Well, actually, at the moment I’m under sedation. I think I suffer from alienation. And although fans mitigate it, a fan is not a good person to have for a friend, because I’m up here and they’re down there, and then they meet me like you’ve met me. I don’t know if you’re a fan of mine or not. And then you find I’m just ordinary… “ He laughed. “And you get very angry. You know, ‘I had this guy up here, and thought he was great, and he’s just ordinary and he farts and everything’. It’s no kind of a relationship for people to sit and wait for words to come out.”

Ivor recalled something that happened to him at Peter Cook’s club, The Establishment, around 1962. “They gave me a show once a week. I’d become well known because of the radio, and at the end of a show a man came up to me all grim. He looked like a Wee Free. He said: ‘My wife’s a great fan, she’d very much like to meet you.’ I looked over his shoulder, and there was this lovely-looking woman, and I said, ‘Sure. I’d be be delighted.’

“He went back and whispered to her. She came forward, all diffident and all sweet. I thought, ‘Wow, too good for him,’ and we talked for about half a minute and then she started getting a little bit worried looking. She said, ‘Excuse me’ and went back to her husband. He came back.” By now, Ivor is talking in a booming comedy voice: ‘I’m terribly sorry, Mr. Cutler,’ he said, ‘My wife finds you a terrible disappointment.’

“It was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Ah lovely to read this and remember him. I hope we still have such unique talent among us for years to come. A real individual.

You have also prompted me to read that book by John Burnside that is staring at me from my bookshelf.