Noise Annoys: nothing says loss of hearing like The Rolling Stones

The first novel by New York author Jonathan Wells is a comic satire about punk rock and hearing aids (among other sensational things).

Jonathan Wells’ first novel is about many things. It is about family secrets. It is about abuse. It is about fathers and sons and brothers. It is about ageing and debt, blunted ideals, the meaning of innocence. It is about the enduring power of Marquee Moon by Television versus the corporate gyrations of the Rolling Stones. All of these concepts blush and bloom, while the story skips and jitters like an early song by Talking Heads. There is anxiety. There is rhythm. The whole thing is held together by a joke so funny it could be true.

It is to Wells’s credit that the trauma at the centre of the story - no spoilers - is held aloft by a comic conceit about a line of hearing aids.

“One of the most difficult obstacles in the hearing aid business is that people don't want to admit that they're ageing and need them,” Wells writes. “But what if we designed a hearing aid that stood out? That was a badge of honour? One that proclaimed that you were proud of your impairment, not embarrassed by it? What if by wearing them you showed the world that you had lost your hearing for something you loved? And that you knew that it had been a worthy sacrifice? A sacrifice for rock and roll? What better reason could there be than that? The theme of our lives. The heart of our youth still beating still alive? Wouldn’t that be glorious? Wouldn’t that transform us from being hobbling ageing men into esteemed veterans, into actors in a great drama?”

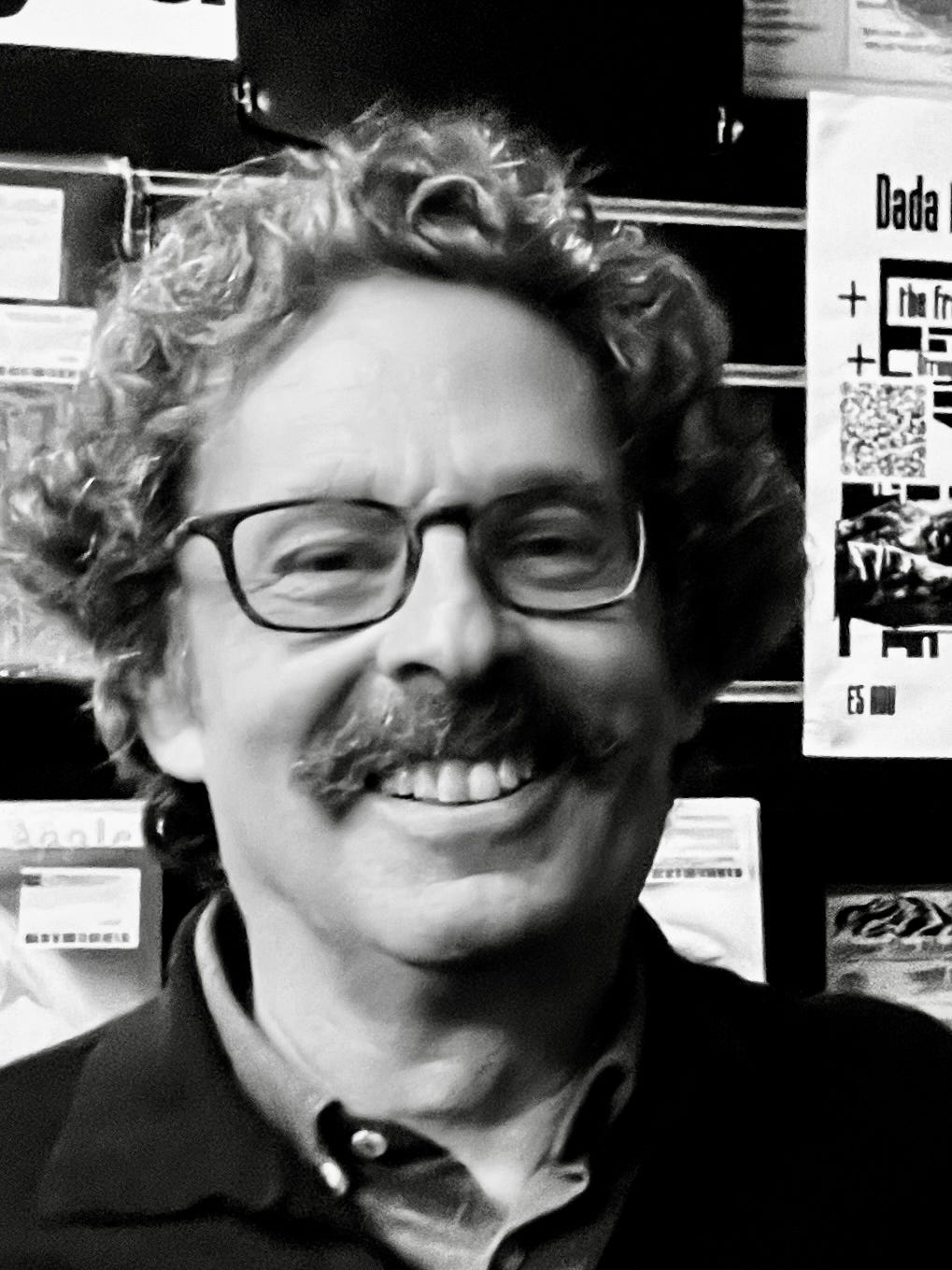

I had questions of my own when I met Wells for his book launch at Rough Trade in West London. Why Rough Trade? It’s possible the irony was accidental. The novel centres on the quest for an appropriate sponsor for the hearing aids, with the most obvious candidate being CBGB, the defunct New York punk club. And here we were with a group of esteemed veterans - a former rock manager, a war correspondent, an actor from Quadrophenia - in the record shop that spawned the independent record business. The walls retain reminders of those times - ancient posters for the Sex Pistols and Siouxsie and the Banshees, and - appropriately for an idea hatched in CBGB, yellowing mementoes of visits by Television, Blondie and the Ramones.

“It’s a record shop,” Wells had said quizzically when we walked in. “I’m not sure I fit.”

It’s true that Wells does not resemble anyone’s idea of a punk. A former director of Rolling Stone Press, he was a poet first, a memoirist second (The Skinny was published by Ze earlier this year), and is now a novelist. “The big leap is from poetry to prose,” he said. “Your relationship to language changes. With poems, you micromanage. In my poems, there’s often not 100 words. So you can test every word. When it comes to longer form and prose, you’re testing for other things too. I never thought I could write a novel, but when I wrote a memoir, which was all true - mostly true - it became very easy to see how to create fiction out of scenes that weren’t true. Fiction allows you to make it up. Of course, if you have no imagination fiction’s a lot harder.”

There is all true, mostly true, and the truth of fiction. In this reckoning of truths, there’s a shadow of memoir in The Sterns Are Listening. Wells was, almost by accident, a veteran of CBGB at the time when the club was the crucible of a musical revolution.

“I really didn’t know of it until my friend moved to New York and urged me to go with him,” he said.

“We took a cab from the Upper East Side, all the way down to the Bowery, which was the other end of Manhattan. It was a warzone. Growing up in the suburbs, it was a place that your parents didn’t have to forbid you to go [to]. You knew enough not to go. Now kids in the city, they had a different approach. They knew the city, they knew the danger zones better, but I was a suburban kid. And there was no way I was going there. Until my English friend moved to New York. It was the first place he wanted to go. Dangerous neighbourhoods in the city didn't mean anything to him.

“The first time I went, there was no line. You just walked in, and it was like walking into a cleaver, a sonic cleaver. It was such an assault that you couldn’t believe it. I just wanted to stand near the fire exit, because I thought the place was going to blow up.

“But then we went again, and David Byrne came on the stage and said, ‘The name of this band is Talking Heads’ and you were instantly completely entranced. And then he started singing in French and it was like, ‘what?’ It was all these things that were irreconcilable. You know, Talking Heads were RISD, Rhode Island School of Design graduates, living in the Lower East Side, like many of the bands. Tina Weymouth, the bassist, was a shoe salesperson at Bonwit Teller - my friend and I used to go and hang out with her during her breaks. I think we saw them in 1975, and then they added the fourth member. But you never knew what to expect [at CBGB], the variety was enormous.”

Wells told me that the idea of a rock ’n’ roll hearing aid sprang from real life.

“I was losing my hearing, and wouldn’t accept blame for the organic decline and felt I needed to blame someone. So CBGB felt like the obvious victim. Then I started to build this idea and I thought, well, that’s an interesting product. And then I thought, ‘No, you’re a crap businessman. Don’t try it. Don’t do it.”

Instead, he inserted the device - carefully, with no trailing wires - in the novel, adding in a further layer of humour, as two brothers disagree about who should sponsor the device. Benjamin, perhaps the more autobiographical of the two, works to gain the approval of the CBGB brand. Spence, the more rapacious brother (and the successful businessman), has his heart set on a larger prize. “Nothing says loss of hearing like The Rolling Stones,” Spence says.

One of the most consequential scenes in the book occurs during a Stones show. Wells writes: “The Stones were hateful, but their fans were worse.”

“Well, you know,” Wells says, “back then you formed friendships on who you liked. And I found that I didn’t like people who liked the Rolling Stones. So that became foundational. But as time went on … I mean, I love them. I saw them many times over the years. But then I saw them in 2012, which is the concert I discuss in the book. And it felt unreal.

“In a giant arena, you see this spindly guy, leaping around the stage, you’re surrounded by awestruck onlookers. It felt thin. Whatever idea of danger and threat that had been in the music felt as if it had completely leaked out.”

In Wells’s book, The Stones concert is the catalyst for dramatic events. Sympathy For The Devil is the soundtrack of the denouement, and also the point where the author invites the reader to consider the metaphorical purpose of his story. It feels, at times, like a reaction to artifice and ritual, a farewell to foolish things. Is it also a metaphor for an abusive industry?

“There’s something of that. But I think that the theme of the book is being heard and listening. There are different aspects that come and go, that improve and become devalued. So it’s logical in a way that music is the vehicle for that. A Spanish writer named Javier Marias wrote an amazing book called A Heart So White. In it he says: ‘Listening is the most dangerous thing of all, listening means knowing, finding out about something and knowing what’s going on, our ears don’t have lids that can instinctively close against the words uttered, they can’t hide from what they sense they’re about to hear, it’s always too late.’

“So there are degrees of hearing. There are degrees of ignoring what you’ve heard.”

The Sterns Are Listening is published by Ze Books, £20

The Stones stopped being dangerous as well as listenable around July 9th, 1969. I’ve no idea why.

Ordered it based on your article!