A Visit to Basque Country - Sex, Cigarettes, and the Nostalgic Allure of Jack Vettriano

A furtive encounter with Scotland's illustrative man

I interviewed Jack Vettriano once. It was long enough ago that he was still insecure about his reputation. (Maybe that never stopped. It’s not a bad flaw for an artist to have). For instance, he was aware that the critic who first promoted his work and helped with a book of his paintings had never actually said that his art was any good. Did I say his work was good? I did not. He was aware of that.

He gave me a moral dilemma. He told me something. And then he made a great play of making me promise not to mention it to anyone. I was aware - perhaps he was as well - that interviews don’t work like that. But it was awkward, and he was insistent, so I said all right, I wouldn’t mention it. A few days later, I went to the opening of his exhibition. My interview had been published, and I had not mentioned The Thing. The artist was a bit cooler than he had been just a few days earlier. There was a bit in the interview that he liked, he said, quoting himself, but not anything that I had written. He seemed a bit crestfallen. I’ve always wondered: did he tell me The Thing in the hope that I would ignore his request and print it anyway? It would have caused a fuss, and I’m still not sure whether the fuss would have been good or bad for his reputation.

So, it took a while, but I found the cassette, a Scotch BX C90. The interview lasts 95 minutes: the batteries in my recorder must have been exhausted. And those 95 minutes don’t include some of the things I remember, the personal stuff about relationships and marriage. All that. There must be another tape. But the tape does not include The Thing.

What I didn’t remember is that there is more than one Thing, because there’s a point in the interview where Vettriano says he will tell me something about somebody - a high-up figure in the Scottish arts world - as long as I turn off my recorder. “Because that really must be in confidence.” So, clearly, some secrets were more secret than others. Or, and I don’t think this is entirely mad, he was telling me the Other Thing because he wanted it to get out. Maybe not directly, certainly not in a recording of his voice saying it, but through the back door of betrayed confidence.

(I can’t tell you this Other Thing, because there is a Watergate-style gap in the tape, a void in my memory, an erasure. That’s my story. If you meet me in an underground car park I might tell you something else.)

The thing is, I knew a couple of investigative reporters back then. Back then was 1994, or maybe 1995. Analogue days, innocent times. Scotland had newspapers and reporters and professional art critics. Edinburgh District Council was involved in a bit of jiggery-pokery with the owners of saunas, which were operating as brothels. Reporting on this business, one of my colleagues had been tasked with visiting a sauna and then, in time-honoured tradition, making his excuses and leaving. He told me that one of the saunas, Scorpio Leisure, had a Vettriano on the wall.

“I’m embarrassed that you know that,” Vettriano said, embarking on a weary explanation of how “under the auspices of research” he had visited the sauna.

“I mean, it’s surprisingly well organised. It was like a sort of badly-decorated hotel lounge, in the sense that it was tacky, but all new and perfectly clean.”

He was “quite fascinated” and listened as the owner told him stories about the sort of men who visited the place. “You’d be amazed at who goes there, bloody amazed.”

And here is The Thing.

The owner said to Vettriano, “On the house”, and Vettriano did not make his excuses. “Well, I like sex. Christ, of course I do, and I was fascinated by it. I mean, the girl was gorgeous. She was gorgeous, and it was on the house. My conscience was sort of cleared, if you like.”

The owner of the sauna, said Vettriano, asked for a favour in return - a painting. So he went down one morning and took photographs before the punters arrived. A couple of girls came in. The painting, Scorpio Club, shows the main area of the lounge.

“I met a guy from the Daily Record down there one night,” Vettriano said. “But, I mean, I don’t … I never have gone down and used the facilities. I go down, and I like to sit in the lounge, because I like to look at the girls, and I like to see how it all ... It really is a fascinating study, because the way it works is … you probably know this. The guys go and they have to get changed into a towelling robe and they come back through into the lounge, and the girls will give them a soft drink or a coffee, and some of the preferred customers get, you know, a glass of wine or a glass of spirit. And there’s this sort of pretend atmosphere. Of ‘Well, how are you?’ ‘What’s the weather like outside?’ And the guy will look around at the girls, and when he’s selected one, it’s a wee nod like this. And that’s it. She goes through with him and they do their business. It’s strange. It never ceases to amaze me how it all works.”

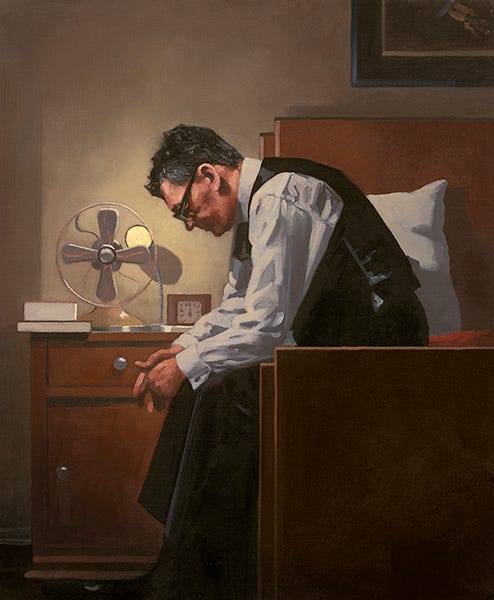

The original title of the painting was Negotiations At The Scorpio Club. Vettriano had a thing about transactions. He liked formalities. He was into ritual.

The interview turned into a negotiation. Vettriano would frame his thoughts, listen to the words in the air, and then try to take them back. He was hyper-aware of how things might look. “Do you have a dark side?” he said to me at one point. It seemed an odd thing to ask; a hard question to answer. It was, of course, something Vettriano was asked all the time.

We talked for a while about prostitution, and saunas, and the air of menace that surrounded the industry, and it felt kind of grubby and intimate and, in ways that weren’t exactly tangible, quite threatening. Where the threat was coming from, and who it might be aimed at, was never clear. It hung like smoke in the air. The negotiations continued. Vettriano smoked cigarettes. The room darkened. Gloom settled over the afternoon.

Vettriano said he was reluctant to give his views about prostitution - “I don’t want my career brought to its bloody knees” - but he felt that the Edinburgh solution of turning a blind eye to saunas was “plainly better than any kind of walking the streets. At least it’s controlled to a degree. The pure fact is, they are very busy places, and what are we to do with that knowledge. Why are they so busy?”

I suggested to Vettriano that his fascination with this insalubrious area would lead critics to accuse him of titillation, or perhaps even pornography.

“Yeah,” he said. “But why? And why not? Because, why is it that during the month of December you cannot buy a basque in Jenners, because they’re all sold out. So I’m told. Now, it’s funny. I can’t help but think that there’s a side to people that they’re frightened of, that they won’t admit to themselves; that they get titillated by stockings, or by a lipstick. They pretend that somehow it’s better to be above that and say, no, no, ‘I don't get titillated, my wife and I respond to each other in a very mature and adult way.’”

Side two of the cassette is less stressful. We went over some of the familiar stories about Vettriano’s accidental career as a derided popular artist. (This never really stopped. The Guardian marked Vettriano’s passing at the age of 73 with the headline: “His paintings are like a double cheeseburger in a greasy wrapper”, an assertion which has the benefit of being snobbery disguised as insight and, to coin a metaphor, a load of old shite). He suggested a few times that he was not bothered by this, as if the act of repeating the assertion would make it come true.

An early supporter of Vettriano was the late W Gordon Smith, critic, collector and general man of the arts. Smith edited the 1994 book Fallen Angels, in which pieces of writing ran alongside Vettriano’s paintings. This meant it wasn’t strictly an art book. There was no critical essay interpreting the work. “It’s interesting,” said Vettriano, “that old WG, as much as people think he and I are married… if you look at his stuff, he’s never ever said I was a great artist. He talks about the mystery and the sexual shenanigans. But he never says ‘he is Scotland’s leading artist’.” Vettriano pulled himself up by the braces. “Christ, he wouldn’t fucking say that, he fucking doesn’t feel that. But he’s never said ‘This guy is’, you know, ‘a force in art’. He’s never said that at all. He is as mystified as anybody that the public buy my work, and all he’s doing is reporting it.

“Nobody’s ever said anything about my place in Scottish contemporary art. But I’ll be honest with you, I don’t bloody well want them to, because I think once you start going down that road, you get into deep trouble. Because I’m nothing to do with Scottish art. I’m just to do with me living in this wee world and painting these wee situations.”

Vettriano’s critique of critics was a constant theme. He was particularly unsettled by something the late Beatrice Colin had written. What it was, he didn’t articulate, but he seemed troubled that a young woman might have misunderstood his intentions. (Vettriano had quite an effect on some women. Listen to his Desert Island Discs and you’ll hear the regal Sue Lawley utter the line: “But you pulled the birds easily.”) Then there was the author of Scottish Art 1460-2000, Professor Duncan Macmillan. He was not a fan. “He’s welcome to paint so long as no one takes it seriously,” Macmillan had written.

“He’s so bloody intellectual about the whole thing,” said Vettriano. “I despair at that. I just think that it’s all bloody irrelevant and nonsense. I really do. He’s always tracing lines between everybody and if he actually knew what it’s like to be an artist … Sure I’ll go along and look at Robin Philipson’s work and I’ll think, ‘Yeah, I quite like the way you did that.’ And I come home and I put it in a bloody painting. That doesn’t trace a line between the Edinburgh School of Art and me. That means I fucking went out and saw it and I liked it.

“There’s so much rot talked. Somehow they have to dress it all up in fancy bloody clothing. And I suppose if he’s speaking about your favourite artist, that’s great. But he came into an exhibition of mine and I’ve never seen anybody turn around quicker. Christ almighty. Whoosh. . I thought ‘Christ he’ll be dizzy,’ he turned around that quick.”

We talked about Vettriano’s journey into art. How his grandad gave him some pencils and paper and he started to draw, and he had a certain skill, and was notably average in everything at school apart from art and nature knowledge, because he was a boy for gathering birds’ eggs, and he fell in with a mediocre crowd. “We weren’t bad boys. But you know, as soon as you discovered pubic hair and cigarettes, it was like your career.”

School was all about streaming, and Vettriano purposely flunked his exams so he could stick with his pals. In his final year, the teachers decided which boys were capable of learning a trade. “And then there were those that went to the building site at the back of the school and were taught how to mix cement. I was in that group.” At age 15, he left school, and his father urged him to get a trade. He went to a test on a Saturday morning at Dysart Town Hall. “And I must have had something, because I got sent a letter saying ‘Do you want a job as a mechanical engineer?’ My dad thought it was like being given a certificate to teach medicine. ‘Son, you did it, you did it! You got a trade!’ Because he was a miner. And that was it, I was away to the pits.”

When Vettriano was 21, he met a woman who was a school teacher. “She saw some of these drawings I had done and she said ‘You really should colour those in, and she bought me a wee box of watercolours. It was Reeves watercolours because, I remember, the box didn’t have Mickey Mouse on the front.”

From that, he progressed to priming sheets of hardboard and painting in oils. It was the time of Surrealism and Dali. Vettriano had a go. “You know, bodies hanging over crosses and trying to pretend that I was really religious. I remember painting an old man’s head with cobwebs across his eyes, spiders on his head. Coffins. All very gothic

“The more I painted, the more I realised that it was just a lot of nonsense. What I began doing was trying to acquire some skills. I used to set myself little exercises, and it was always to do with trying to make something look exactly like it was. Like an apple, I had to make it look like an apple. Which I suppose means that I never had any lecturers standing over me and saying, ‘There is no reason, my boy, why an apple must be green and brown. You can make it square if you like.’

“I only ever want to do things that look like things, and I can’t, for the life of me, see anything in any other kind of art. No, I just can’t see it.”

Winding forward, Vettriano got married, lived in a semi-detached, mimicking Monet in the garden shed. At the age of 37, perhaps wondering whether he would ever drive through Paris in a sports car with the warm wind in his hair, he sold two pictures in the Royal Scottish Academy summer show. He adopted his grandfather’s name, replacing Hoggan with Vettriano. He grew his hair, became a dandy. He was now an artist, or - at least - his idea of what an artist might be like.

He had also found his subject matter. The two paintings were called Woman In A White Slip and Saturday Night.

“Saturday Night was the interior of a dance hall, or my memory of it. This was when to go dancing meant going to one of the little ballrooms. You know, there’s a guy in the middle of a stage with a turntable, and then you got a band come out and doing cover versions all night. Because they didn’t have clubs, the only places you could do it was in these old ballrooms that were used previously for the ballroom dancing. So you had all the Art Deco fittings and the brass railings, that kind of thing. And listening to, dare I say it, Beatles music, and loving it.”

Selling the paintings was a moment of validation. “I thought, Christ, people do want to see my image of the world I lived in, or live in. And I just started to kind of explore.”

At first, Vettriano said, he played around with landscapes and still lives, taking photos in the country and trying to reproduce them in paint. But then his imagination took hold. “You know, like the Scorpio Club and stuff going right back to days on the promenade.”

It wasn’t a grand plan. “I found myself in it, and having to respond to it. I couldn’t now paint a still life if my life depended on it, or a landscape. It has to be people and they have to be in some way involved in rituals of courtship. The only time I deviate from that is doing a single portrait of a woman, and even then, I’m likely to put in the odd wee article which suggests something.”

“If I was to do a computer search of your reputation,” I said to Vettriano, “the phrase ‘chocolate box’ might come up.”

“Oh!” said Vettriano. “Oh! Who said that? No, don’t tell me.”

“It might have been you,” I said.

“I did say that. I said that to Gordon.”

I suggested to Vettriano that even in supportive critiques of his work, there was a mood of cautious encouragement, and a sense that in the categories of art college degree show, he would be categorised as illustration rather than art.

“Well, because of my way into art,” Vettriano said, “I can’t see that distinction. I can’t see it even now that you’re saying it. People have said to me, ‘it’s funny, they look like posters’. I wouldn’t disagree with that at all. If one of them said ‘Casablanca’ over it, or had ‘Humphrey Bogart’ at the bottom, I couldn’t disagree.

“I’ve copied everybody, from Dali to Van Gogh, Monet, all the Impressionists, bloody Whistler, Sickert; I’ve copied their work. And what I developed is a bastardised hotchpotch. One of the interesting things is, it’s identifiable. People know my work at a distance. That’s all by accident.”

He talked about a biography he had read of LS Lowry, and how there were parallels. “He was a rent collector all his life, just painting in the evenings and at weekends. And somehow, because he never spent those four years under the tuition of somebody, there is something that’s not quite valid” about his paintings. “They’re a wee bit Sunday-ish, a wee bit shamateurish, and not quite to be taken seriously.”

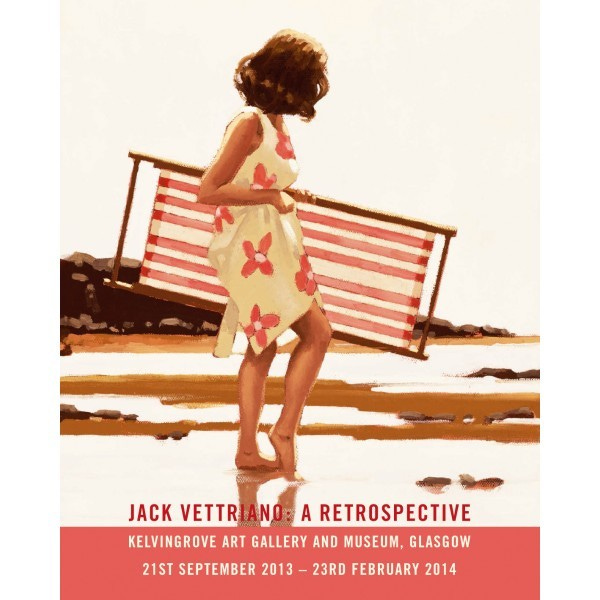

I suggested to Vettriano that his beach front paintings were quite generic. They didn’t seem to portray specific places.

“My beach fronts? They’re not, in fact. I really should go to more bloody beach resorts. I mean, I’ve been told that. I think Scarborough has a lot of it under preservation. I should go there and bloody look at it. But you see the background to my work never has had a lot of elements. It’s the people that are relevant. It’s like a play. You know, like, design that backdrop, drop it behind them, and that’ll do. It’s sort of: right they’re by the seaside, so get the sea in there. I don’t sit and think then, let’s have a rock like that, and a wee tearoom at the end of it. It’s just my way of saying, yeah, there was a tearoom there, and it was green. All the council stuff was painted green. There’s no great significance in that. It’s just trying to make sure that the viewer damn well knows it’s a beach.”

And the sense of time? If the characters were the important thing, when were these scenes taking place? They seemed to have a nostalgic glow.

Vettriano flicked his lighter, sparked up a cigarette. “I think that has come about because, I personally like that period. I like to dress in waistcoats and braces, and I like to know that women are wearing stockings and stilettos, and that everybody smokes, and that Glen Miller’s on in the background. That’s all that is. It’s nothing more or less. You could say, ‘Oh yes, a wee bit of escapism there, Jack’. And, yip, you’re right, because you’ll never see me out there with my shirt tail hanging out, and my bloody baseball cap on the wrong way round. I can’t abide all that. It’s why I like the Beatles. I’m caught in a time warp and, and I can’t really see a lot wrong with it.

“It’s not that I need to change or I’ll become extinct. I don’t need to change. I’m doing okay, and I’m happy with my bloody second hand suits and stuff. That’s allowed. There comes a point when you have to give in to age and say, ‘Well, I’ve got no intention of responding. I just like this sort of world, and I try and recreate it. That’s all. That’s why in the paintings, the model always looks glamorous and sexy. Because I like that. Simple as that. I wouldn’t paint a woman that didn’t look like that. I’m just entertaining myself, in a way.”

“So,” I said to Jack Vettriano, “would it be overloading things to say that you’re yearning for a time when you could go to the beach and everyone would have a hat on?”

“I think that would be a mild overload,” Vettriano said. “I would like that. I would like to go back to the ballroom I first went dancing in. I would like to go back to the days where they played three slow records and then three fast ones. Everything’s so fast now, and the music, you can’t make head nor tail of it. People are rude. Nobody every says ‘would you like to dance?’ anymore. Men go up and dance with men. Would you do that? I couldn’t do that. I would feel bad. I’d be looking around me, thinking I hope nobody sees me. In my day, and in your day probably, dancing was simply a convenient way to get yourself in front of a girl that you liked. Whereas now, they dance for dancing’s sake. I find that difficult to understand. Different if you were doing tap, or something skilful. But when you lie and crouch your shoulders up and spin on your spine, I think there’s something suspect about that.”

In the end, Vettriano suggested, we were discussing the difference between commerce and artistic credibility.

“It’s like Cliff Richard versus Leonard Cohen, “ he said. “I mean, I like Leonard Cohen very much, but I’m also able to see that Cliff Richard has given more people more pleasure than Leonard Cohen ever will. He’ll never give me as much pleasure as Leonard Cohen gives me, but in terms of the world, no doubt about it.

“But then,” Vettriano said, suddenly recognising the absurdity of his argument, “I’m not the Cliff Richard of art!”

I really enjoyed this. Thanks for sharing.

Enjoyed reading that, Alastair. The Thing about Vettriano… it will run and run.